- Home

- Ninie Hammon

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Page 9

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Read online

Page 9

‘Cept their houses was just empty, not old. And their wives hadn’t come back like Abby had, so she was right there inside Shep’s head. He sat now listening to her speak out his mouth, asking after Doodlebug’s youngest, Effie, who had some kind of heart problem, and wanting to know if Jim Bob’s mama’s gout was still bothering her and did Billy Ray ever find his bird dog that’d run off.

“I ain’t had no home-cooked food in a month of Sundays,” Claude said, piling his plate high with fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, fried okra and black-eyed peas.

“That what you come back for, Claude?” asked Billy Ray. “Missed cornbread and buttermilk, didja, locked away in the nut house like you was?”

Claude’s cousin speaking to him like that had ought to have got under Claude’s skin, but it didn’t.

“I come back because this here’s my home and I got as much right to be here as anybody else at this table.” Then he glanced at Shep. “Least that’s what I thought I’d come back for. But when I showed up and found things the way they is, I figured out I come here for some other reason I didn’t even know, some” — he stopped and grinned — “higher purpose.”

“Just what purpose might that be?” Doodlebug asked.

Uncle Virgil chided his sons. “Now, boys, you act like you ain’t glad to see your cousin.” Which they weren’t and weren’t putting up a very good show of hiding it.

“Any of you interested in getting all the people back who’s disappeared?” Claude asked, with his mouth full of mashed potatoes. That was a conversation stopper. You coulda heard a mouse in house shoes tiptoeing across a cotton ball in the silence that followed.

Jim Bob lived in Frogtown with his wife and two boys. Ronnie and his wife, Becky Sue, lived with his parents and sister on Elkhorn Road. All them people was gone now.

“‘Course we are!” Jim Bob said. He looked around the table. “It ain’t like we ain’t been trying! We all went to the law and reported it.” He sneered at Claude. “You think you can do a better job of getting help than we did, you go on ahead — and they’ll throw you in a cell with the Caswell brothers, Truman Pettigrew, and I don’t even know who all else. Or haul you off in an ambulance like they done them folks from Wisconsin who come looking for their granny.”

Some of the Nowhere people who’d lost families didn’t take it real well that the state police didn’t do nothing. They’d got ugly about it and got locked up. And they was some away-from-here folks who kept going back and forth across the county line until they gave up because they got sick — vomiting and nosebleeds and such.

“It’s powerful queer,” Aunt Pauline said, filling up her husband’s glass of ice tea. “The law comes and they see it. They see ain’t nobody there, houses empty, everything gone. They ‘investigate’ and write it down and then they never come back with no help.”

“Their remembering’s gone,” Uncle Virgil said.

Aunt Pauline nodded. “They come down with the forgets and don’t know nothing about what they seen, throw their reports in the trash, I guess, ‘cause they sound so crazy.”

“When you go back to ask why didn’t they do what they said they’d do, they look at you like you’s the one lost your mind,” Uncle Virgil said.

“Them Wisconsin folks musta seen that they granny and everybody else was missing and then forgot they seen it,” Aunt Pauline said. “So they come back a whole bunch of times. The forgetting must be hard on you ‘cause after awhile them folks was half dead.”

“We don’t need all them outsiders to fix our problem,” Claude said, piling another helping of okra on his plate. “It’s up to us to do it ourselves, our way.”

“And what way is that, Claude?” Jim Bob asked. “You know where they at, do you — all them missing people?” His voice dropped to a whisper. “You know where my Jenny is — Derek and Jason?”

Shep told 'em then. “Abby talks to me.” He got the expected disbelieving, sympathetic looks. He tapped his temple. “She’s in my head. You can believe me or no, but she says all them people that’s gone is still right where they was — we just can’t see them.”

“That’s crazy!” Doodlebug said.

“Any crazier than a whole county full of people vanishing in the first place?” Claude said.

“And nobody remembering what they seen here soon’s they cross the county line?” Shep said.

Didn’t nobody have an answer for that.

“They’s a thing called a Jabberwock’s got them.”

“You done lost your mind, Shep.” Jim Bob shook his head — sad-like, not mad.

“The Jabberwock told my Abby it’s gonna let them all go.”

“When?” Ronnie demanded, his voice cracking with emotion. “Becky Sue’s pregnant and the baby was due a week ago.”

“Not when … if.”

“If what?” Billy Ray asked.

“If we keep folks from meddling in the Jabberwock’s bidness,” Claude said. “It don’t want all them people it took. Never did want ‘em all. It just wants three of them, but it’s gonna hang onto every mother’s child in Nowhere County unless …”

“Unless what?” Aunt Pauline asked.

“Unless we leave it alone. They’s folks buttin’ in what don’t concern them. One of them’s Cotton Jackson and another is Pete Rutherford’s daughter. Third one’s an outsider, a black man married to a white woman.” Claude spit on the floor after he said it.

“How are we supposed to stop ‘em from meddling?” Uncle Virgil wanted to know.

“Shoot ‘em,” Claude said, matter-of-fact as pass the cornbread. “That’s why me and Shep is here. We ain’t got no hardware no more. Everything of Shep’s …” He let the sentence dangle. Nobody needed an explanation. “You still got yours, though. And we need to borrow some.”

“You want us to supply you with guns so’s you can walk out that door with ‘em and shoot somebody — that what you sayin’?” Uncle Virgil was having a hard time wrapping his mind around a request like that.

Claude smiled, revealing his hoary mouth with missing and rotted teeth.

“Yup. That’s what I’m sayin’.”

They was a rumble of thunder outside, rattled the window panes. Shep wondered if maybe Abby’d done it, made it thunder. He suspected she could if she wanted to. He suspected there wasn’t nothing anymore that Abby couldn’t do.

Chapter Nineteen

“I hate Forrest Gump!” Douglas Taylor said, and kicked a rock down the steep grade of the hillside to watch it plunk into the creek.

“Awe, come on,” said Rusty Sheridan. He nudged a bigger rock with his toe to loosen it, then shoved it off to dive in behind Douglas’s. “It’s like one of the best movies ever … that part where he’s on the shrimp boat and he sees Lieutenant Dan on the dock and he just—”

“I didn’t say I hated the movie. I said I hated Forrest Gump — the guy, the character.”

Rusty knew Douglas didn’t really hate the movie or the character. He hated the character’s haircut — and that was certainly understandable! That haircut had made Douglas Taylor the laughing stock of Carlisle Middle School. Well, not just the haircut. Douglas already had a couple of strikes against him. He was — what was it Rusty’d heard Fish call Mrs. Gillespie that time Fish was mostly sober? Rotund. That was Douglas alright — rotund, with rosy, round cheeks. And his totally clueless mother actually called him “Dougie” in public. At school! She engaged in a lot of public affection, too, which landed Douglas the nicknames Huggie Dougie and the Hugable Dougable. Rusty’s mom had said Douglas’s mother was “half a bubble off plumb” and Rusty’d told himself to remember that phrase so he could use it to describe his friends when they acted stupid. Douglas’s mother was more than just stupid, though. The way she acted about Douglas, wouldn’t let him play in the mud, for crying out loud, or drink out of a water hose, said she was protecting “her baby” from germs. That time he and Douglas had climbed a tree and she called the fire department to get Douglas dow

n — the look in her panicked eyes, Rusty believed that day that she was genuinely crazy.

But even if the woman was only clueless, she’d outdone herself in cluelessness a couple of months ago. Rusty was sure it qualified as some form of child abuse. After she saw the movie, Claire Taylor had told the barber to cut little Dougie’s hair “just like Forrest Gump’s.”

Rusty stopped, felt like he’d been kicked in the belly. How long would it be before the reality of J-Day was no longer shocking? How long would it take before it was just ho-hum: “Yeah, that’s the way life used to be but not anymore, we’re stuck here — bummer.” Well, it would take longer than two weeks for Rusty Sheridan to stop feeling nauseous every time he thought about it! And he thought about it a lot, because it changed everything.

It didn’t matter anymore how Douglas wore his hair, or if his mother hugged him in public or if … nothing like that mattered now that he and the rest of the kids in Nowhere County couldn’t go back to school in Beaufort County in the fall. Not as long as the Jabberwock stood in their way. And how long would that be?

“I think Forrest Gump is a … a … jackass,” Douglas continued, and was right pleased with himself for being able/willing to use the word. Rusty tried to act suitably impressed. Douglas was only ten and didn’t have a really firm grasp on profanity, its nature and its uses. He only knew he wasn’t supposed to say certain words and so, duh, those were the words he tried to drop into any and every conversation.

At twelve, Rusty was far more advanced in the skill of cursing. When his mother, Sam, was out making her rounds all over the county as a home health nurse, Rusty used to stand in front of the bathroom mirror and practice dropping cuss words in between the syllables of regular words — so it sounded smooth and natural when he did it around his friends, like he talked that way all the time. He didn’t, of course, and in point of fact neither did any of them. Boy talk at home and boy talk among friends was—

Friends. He wouldn’t be seeing his Beaufort County friends until … unless—

The Jabberwock.

He shivered and tuned back in to Douglas’s prattle, which was more or less nonstop, a background noise that Rusty mostly ignored.

“— time to grow out by then.” Douglas grabbed a hunk of his blond hair — the part that was long enough to grab.

Forrest Gump was a great movie and all that — and Rusty would watch Tom Hanks take a dump! — but surely no one would dispute that his haircut was nightmare material. Shaved down to like an eighteenth of an inch from his ears halfway to the top of his head. The hair on the top was hardly long enough to need combing. Well, except for the two years when Forrest was running back and forth across the country — didn’t cut his hair and grew a beard.

In the beard department … Rusty had found two black hairs on his upper lip last fall and had been so excited he’d named them. But so far, none of their friends had shown up to join the party. He checked every morning in his mother’s magnifying makeup mirror.

Rusty’s hair wasn’t as long as Forrest’s had gotten then, either, but it was thick — and curly, which he hated! At least his mother let him wear it long-ish, down into his collar. It wasn’t red anymore — thank you, Lord! — like it had been when he was a toddler. That’s when he’d become “Rusty.” First name Russell, red hair — Rusty was inevitable. Gratefully, his hair color had darkened as he got older and now it was just brown, though in bright sunlight you could still see red in it.

Oh, he thought his mother’s red hair was gorgeous. She looked beautiful with it hanging down smooth around her face. But she was a girl. Red hair was fine for girls. If it was real. Douglas’s mother dyed her hair a shade of red Rusty’s mother called “a Sears color” — meaning it wasn’t a color found in nature. It’d been blonde when she and Douglas lived across the street from Rusty in the Ridge, with her husband — what was his name? Rusty couldn’t remember. He’d been the second one while they lived in that house and now she’d married somebody else altogether and had moved in with him. Which was why Rusty’s mother had to bring him out into the boonies past Twig this morning to spend time with Douglas. It’d been her idea and Rusty knew why. She felt bad that his life had pretty much fallen apart, but things were tough for everybody now. She thought she had been neglecting him ever since …

The Jabberwock.

It was out here somewhere. The Beaufort County line was only about half a mile away. Which was why Douglas’s mother had strictly forbidden him to play in this part of the woods. Which, of course, was why Douglas had demanded they play here — you got your little victories wherever you could. Douglas had wanted to go see the Jabberwock, but Rusty put the kibosh on that, told him you couldn’t see “a mirage” in the trees — which wasn’t strictly true. You could if you knew what to look for. Rusty knew. He’d seen it lots of times. But more important, he’d seen what it could do lots of times, had been with his mother at the clinic in the Middle of Nowhere when they had an “incoming.” Somebody who had accidentally stumbled into it — he supposed things like that happened. It was more likely, though, that they’d decided to make a break for it. But it really didn’t matter what their reason for challenging the Jabberwock was, the result was always the same — the just-shoot-me experience of projectile vomiting in front of people. Or maybe just suffering the mother of all nosebleeds. Or going blind and deaf. There were lots of menu items. But the single worst thing Rusty could imagine was throwing up with an audience. He would rather die.

What if he was sitting on the bench in the bus shelter up-chucking on his brand new Air Jordans and Whitney Malone was there and she had to leap out of the way so the puke wouldn’t splatter on her? He was picturing the horror of that when he heard the sound. The rattle. But by then it was too late. The rattlesnake had already struck.

Chapter Twenty

When Hayley was little, she thought her father was Atticus Finch from the movie To Kill a Mockingbird. They’d taken her to see it and when Gregory Peck walked into the kitchen in the first part of the movie, Hayley had disrupted the whole theater pointing at him and crying, “Daddy, Daddy.”

Duncan Norman looked a little like Gregory Peck, he’d always supposed. Dark hair, thick eyebrows, a carved face, tall, thin lips more accustomed to frowns and severe looks than smiles. He had always thought that’s where the resemblance lay, in the facial expressions, not the structure. Atticus Finch was a man who stood his ground for his principles, just like Duncan Norman stood his ground for his spiritual ones. Both men were willing to fight for what they believed in, were not cowed by opposition.

Both men adored their little girls.

Duncan heard a sound come from his throat, a kind of strangled sob he didn’t even recognize as his own, though it must have been.

He thought about Atticus reading to Scout when she was little so often she had learned to read before she entered first grade, and had gotten in trouble for it. He had read to Hayley, too, when she was little. Every night. Bible stories and Grimms’ Fairy Tales and The Hobbit. She hadn’t gotten in trouble because of it but she had gotten a bald spot.

His eyes swam with tears at the memory of the little thing — pale and thin, with all manner of congenital digestive issues that made processing food a challenge — and no hair on the top of her head. He and Miriam and the doctors were convinced it was yet another manifestation of the malfunctioning gall bladder or pancreas or liver. She was hospitalized. Batteries of tests turned up only the usual suspects that would eventually doom her to a life of obesity. Nothing indicated a cause for her hair falling out.

Then Duncan figured it out one night as she sat in his lap in the platform rocker, so still, her breathing so slow and even that he often thought she had fallen asleep. But she was absolutely alert, heard every word as he read to her … resting his chin on the top of her head. His chin with the day’s growth of beard. Which was systematically sanding off her thin growth of blonde hair.

They’d all laughed about it.

He even teased her about it now, sometimes, asking if she’d checked the top of her head for hair lately.

The image of the little girl with a bald spot was overlaid by the image of the … the …

Why hadn’t he listened to Sam Sheridan? She’d warned him, told him not to go barreling down to the funeral home, rushing to his daughter’s side.

He remembered her words distinctly and the intensity with which she said them.

“Your daughter is the girl whose picture you carry in your wallet. That’s Hayley. That’s the Hayley you want to remember. Please, please don’t spoil that image forever by—”

But he wouldn’t listen. Stubborn. Defiant. Since he was always right — and the Reverend Duncan Norman was, after all, always right — he didn’t listen to the warning, gave in to the horror of need in his chest to be with his little girl, to see her—

And he had seen.

He hadn’t let Miriam go in. Thank God for that. He had made her wait in the car.

There was no face on the head of the person lying bloated and stinky on the metal tray.

No face. Her head bashed in on both sides.

A body, battered and bruised and broken.

He felt something wet in his hand and opened his clenched fist to see blood on his palms. He had squeezed his fingers into such a tight fist that his fingernails had cut into his flesh.

But there was no pain. Didn’t feel a thing.

The pain in his chest, his belly, his heart, his whole soul was so great that he could have cut off his hand and he would have felt nothing at all.

“Duncan …?”

The words came in a soft voice from behind him. It was Miriam. There was such need in that lone word he wanted to turn and run away from her. Felt as if she were sucking all of who he was, his whole being out of himself with the power of her need to be comforted in her loss. Their loss.

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

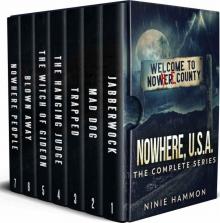

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material