- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Read online

Mad Dog

Nowhere, USA Book Two

Ninie Hammon

Copyright © 2020 by Sterling & Stone

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

The authors greatly appreciate you taking the time to read our work. Please consider leaving a review wherever you bought the book, or telling your friends about it, to help us spread the word.

Thank you for supporting our work.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

The Series Continues…

A Note from the Author

About the Author

Also By Ninie Hammon

Chapter One

Judd Perkins was a level-headed man. Literally. Well, flat-headed anyway. Maybe it was because his mama left him lying on his back for too long when he was a baby. That’s what folks said caused a kid to have a head that was flat in the back. Judd’s was and maybe that was why. It suited him, though, built solid as an anvil like he was — thick and broad, with arms like sides of beef. His late wife sometimes had to work a seamstress’s magic to get shirts to fit around his broad shoulders. If he’d been a tall man, he’d have been a giant. At five feet ten inches, he just looked like — what was it Julie Ann called him? — a refrigerator with legs.

And level-headed people didn’t get all upset over nothing. Which was what Judd was afraid he was doing, getting all bent out of shape over something didn’t mean a hill of beans.

But what if it did?

Judd had lost his pickup truck on J-Day, had been on his way to load up two rolls of baling wire from a fella in Drayton County, crossed the county line and boom! Wound up in the Middle of Nowhere sicker than he had ever been in his life. So sick he was heaving and praying to die at the same time, with a needle buried so deep in his skull that he still found himself walking around careful so he wouldn’t dislodge it, and that’d been almost two weeks ago. He had an old farm truck, a 1961 International Harvester that wouldn’t go into fourth or fifth gears because the transmission was shot, but it had a full tank of gas and would get him from Point A to Point B when the need arose. So he could take Buster in to see E.J. — Dr. E.J. Hamilton, the veterinarian — if he had to. He just didn’t know yet if he had to.

He took off his John Deere cap and wiped his forehead with the back of his hand, squinting up into the woods where the dog had run off to. Just run off. That wasn’t like Buster. Taken all by itself it wasn’t no thang. But with everything else.

Squinting, he thought he could see the white fur of the big dog in the shadows of the trees on the edge of the woods, but he couldn’t be sure. He opened his mouth to call out, “C’mere, Buster!” but he didn’t. Maybe he’d ought to talk to E.J. first.

“Either crap or get off the pot,” he said aloud, would have said it to Buster, who’d have wagged his tail and cocked his head to the side like he understood every word. “Either call the vet or no, ain’t no sense in stewing over it all day.”

He had a lot to get done today, and he found it hard to concentrate, his mind wandering off to that thing wrapped around the county that you couldn’t cross, in or out.

It’d been there for two weeks now. And even the likes of Judd Perkins was … scared. He knew he wasn’t the only one’d started thinking ahead, wondering how … if it didn’t go away soon, how … everything? He’d never stopped before to consider how systems worked, how loaves of bread got on the shelves and what you could buy with a dollar, and where them big tanker trucks that showed up at the filling stations got the gasoline they pumped into them underground tanks.

He didn’t know how any of that stuff worked, but figured it was all gonna stop working pretty soon and where did that leave him and his family? Wasn’t nobody but his daughter, Doreen, and her girls Julie and Michelle here in the county.

The nine-year-old was taking the Jabberwock thing harder than her older sister. Michelle’d been taking piano lessons and turned out she was real good, and was on some kind of team, soccer or something. At twelve, Julie was preoccupied with rock music and the group of neighborhood girls she ran with, who, the best Judd could tell, would have snared gold medals on the Olympic giggling team.

But Michelle … the scariness of it. ‘Course everybody was taking it hard, but the kids was the ones with the wildest imaginations. He’d heard some of the stories they’d cooked up — about extraterrestrials like E.T. except with acid for blood and two sets of teeth. Or zombies. In the beginning, the first few days, Judd just wanted it to hurry up and get over with so folks could go on with life. That wacky storm had blown something in here — somehow. He’d been sure eggheads would spend years trying to figure out what it had been. Whatever it was, there would come along another storm to blow it back out in a day or two.

Only that didn’t happen. Day after day, that didn’t happen. Now, whenever Judd let himself think about it too long, that big vein on his temple would commence to throbbing and he imagined he could feel again that needle inside his skull.

His Mildred had been gone for going on eighteen months now, so it was just him and Buster. Doreen’s lowlife ex-husband was out there in the wide world somewhere. Doing something. Doreen was doing nothing, sitting home because she couldn’t go to work in Carlisle at the bank where she was a loan officer. So how was she gonna get paid? And what good did “paid” do?

He was gonna talk to her about moving back into the old house with him instead of staying in their little house on Coal Run Road in Pine Bluff Hollow. Wasn’t no sense in that. Whatever was coming, he wanted them close so he could look after them. He could hunt. Woods was full of game and wasn’t a better shot in the whole county than Judd Perkins. He had a garden. They wouldn’t starve. But the rest of it. He just flat out didn’t know.

Buster’d been acting weird for the past few days and Judd’d had too much on his mind to pay it any attention. But this morning the dog had killed a chicken. Just killed it. The chicken was out pecking at whatever it was chickens pecked at in the yard, and the next thing you know, Buster’s leapt up and killed it, snapped its neck and slung his head back and forth with the chicken’s body in his mouth, feathers going every which way. He’d dropped it then and walked away from the body lying there in the dirt. He was walking funny, too.

If there was something wrong with Buster … Judd didn’t know how to think about that. He loved Buster like he was a kid, had hugged that dog to his chest and cried into his fur when Mildred passed and wasn’t no human he woulda done that with.

Buster’d been a beautiful dog when Mildred was alive to care for that long coat of his, brushed it two or three times a week. She had taught that dog all kinds of things, got a book about training a g

uard dog and talked to E.J. about how you was supposed to use commands in German so couldn’t nobody else control your dog. White as a polar bear, the dog was. A Great Pyrenees, he probably weighed 170 pounds, with a big, square head and eyes that followed Judd’s every movement, wide, intelligent eyes that you could look into and … sometimes Judd thought that dog could read his mind.

Buster wouldn’t look at him this morning, though. He’d put the dog’s food out, set the bowl on the floor and Buster wasn’t interested. Judd cast a glance up into the woods at the white spot lying in the shade of that sycamore tree … what was the dog doing up there?

Then he turned on his heel and marched into the house to the phone.

E.J.'s receptionist, Raylynn Bennett, answered, “Healthy Pets Animal Clinic, may I help you?”

Judd swallowed. “I need to talk to E.J. Something’s wrong with Buster.”

Chapter Two

Harry Tungate wondered how long the gasoline would hold out. Not long, he wouldn’t think, and then what was everybody supposed to do? As he bounced down into the potholes in Rooster Run Road on the way to Abner’s place, he was running over in his mind all the consequences of being stuck here in Nowhere County. Couldn’t nobody get out. Couldn’t nobody get in, neither, and he wasn’t sure which was worse.

The Jabberwock.

He didn’t know how it’d got named that — somebody said it’d been Holmes Fischer, the county’s token homeless person, who’d come up with it and if it had been, Harry wasn’t surprised it was weird. He’d always thought Fish was half a bubble off of plumb, even before he started soaking his brain in booze. That’s the kinda thing Fish woulda said.

A hound-faced man with a bulbous nose that didn’t have nothing to do with drinking, Harry had droopy eyes that made him look sad, or sleepy or slow on the uptake, and he was none of those things. His hair was the color of a ten-penny nail and it was getting real thin, but his twin brother Roscoe had lost even more hair — right in the center of the top of his head in the back. You could see pink showing through there like he was an antique car that’d got a bad paint job. The men had identical round bellies hanging out over their belts. But what didn’t nobody know except Harry’s late wife, Beatrice — God rest her soul — was that Harry had a tattoo on his belly right above his belly button. It was an eyeball. Just an eyeball. He’d been drunk when he’d gotten it, so he wasn’t sure anymore why he’d thought it was a good idea, but he did remember it had something to do with the eyeball looking like his naval, or maybe it’d been the other way around. He was grateful that his mat of turning-gray chest hair come down far enough on his belly to hide the danged tattoo so you couldn’t see it if you didn’t know it was there.

Glancing down at the fuel gauge on his old truck again, he shook his head in dismay. A quarter of a tank. Now how in the Sam Hill was he supposed to get back and forth to town once the tank ran dry? Ride a horse? He had a horse, which made him a sight better off than most — along with a farm full of other animals. But wasn’t no way he could use old Buttercup as a means of transportation!

They’d better get this Jabberwock thing fixed soon or everybody in the county was gonna be in a world of hurt for real — not just panicked Chicken Littles scared the sky was falling. Not surprising folks went a little crazy for the first week or so, saying it was an alien invasion or a zombie apocalypse or the government was testing something that went haywire or the time of tribulation had started for the return of the messiah. Things like that. Willard Crump’s wife, Ethel, had run down to the root cellar and hid soon’s she heard people was vanishing and then reappearing, crying and hollering and carrying on, wouldn’t come out for nothing. Far as Harry knew, she was still down there. Billy Dan Singleton took his souped up, NASCAR-wannabe Chevy and was doing almost a hundred miles an hour when he crossed the county line and hit the mirage — spent the rest of the day puking blood out his nose in the Middle of Nowhere, his fancy car gone wherever all the other vehicles had gone.

Harry thought maybe it was toilet paper that finally got folks focused on reality instead of wacky stuff. Hadn’t been for Viola Tackett, wouldn’t have been a roll of it for sale anywhere in the county by sundown on the day after J-Day. His brother Roscoe’d been there and told him all about it.

Viola had honorable intentions when she went to Foodtown in Persimmon Ridge the day after the Jabberwock sunk its sharp teeth into Nowhere County. She needed groceries, same’s everybody else. Oh, she had plans for that store, for all the stores in the county, just wasn’t ready quite yet to pull the trigger on them.

But when she got to the store, the parking lot was full and first thing she seen was Truman Haggardy come out to his truck and start loading toilet paper into the back of it. Them big, mega packages with three dozen rolls each. He had his whole basket full of them, enough toilet paper to wipe his butt until the Second Coming.

Mary Ellen Sweeney come out after him with her cart loaded with canned goods, all the way up to the top, and her oldest, Sue Ann, was right behind her with another cart loaded just as high. The ones quickest on the uptake had figured out they’d better get theirs before the shelves was bare, which would mean the whole county’d have to walk around with crap in their shorts before long because Tru’d bought up all the toilet paper.

That wasn’t at all neighborly of Mr. Haggardy. He’d ought to thought about his fellow man before he done a thing like that and Viola intended to remind him of what the good book said about loving your neighbor.

“Neb, you go get that toilet paper out of Tru’s truck and take it back in the store. Obie, you get them cans from Mary Ellen. Zach, you come with me. I’m going to have me a little talk with Oscar.”

Them folks squawked like stepped-on hens when the boys started doing what she said, yelling about how they’d paid for it, didn’t steal it, it belonged to them. But every mother’s child in the county knew better than to cross a Tackett.

Viola’d marched into the store and seen a line of people waiting to be checked out, carts loaded to overflowing. She stood at the front of the store, not saying nothing, just motioned for the bag boy and told him to go get Oscar Manning, who owned the store. Oscar come running like a lap dog. He was one of them men who went ahead and shaved his head when he started losing his hair because he thought bald looked better. It didn’t.

“You just gonna let them do that, hoard up stuff like that?”

“They ain’t looting,” he said. “They’re paying for what they’re taking.”

Yeah, with money. Which was a thing too big for Viola to get her head around. What was the value of money? Maybe the value was in the fact that the folks using it thought it was valuable. And that worked, she supposed, long’s folks had a reasonable supply of it. But most of the population of Nowhere County — which wasn’t more than a couple thousand people, if that, she didn’t care what Pete Rutherford said — was on the government dole and when them checks stopped coming, what then? They already gamed the system best as they could with liter bottles of Pepsi. Go to the grocery store the first couple of days of the month, when the checks come, and everybody you seen had carts full of Pepsi. They’d buy the Pepsi for $1.99 a bottle using Food Stamps. Then they’d wheel the carts around to the back of the building and sell the bottles back for $1.50 cash. They’d use the cash to buy whatever they wanted — used to be that was booze and cigarettes but lately that’d changed to drugs — and Oscar pocketed the difference.

Not drugs. Drug. OxyContin, and Viola had seen that one coming a long way off. She had eyes and ears everywhere and for the past couple years the free clinics in all the counties in Eastern Kentucky had seen an avalanche of people addicted to the prescription painkiller. She had herself a right good stockpile of it and now them little white pills was solid gold.

Wouldn’t be long before the addicts in Nowhere County’d be looking for other ways to feed that craving. Booze and weed. She had the market cornered on them, too, and those was “renewable resources.” Poor sub

stitutes, but you’d take what you could get when you’s hurting bad as them folks was gonna be hurting. She’d already been thinking about that, which looped back to money. Was money going to matter anymore? What was it folks would turn to when wasn’t no money left or it wasn’t worth nothing?

Could be a lotta things. Shoot, might even be something stupid as toilet paper. But whatever it was, she was gonna be first in line to secure control of it, and allowing people to hoard up stuff might be she could use later was not in her best interests.

“Now, Oscar, you ain’t thought this through all the way to the end. Until that Jabberwock thing goes away, this and the Mini-Marts, 7-11’s, Tuckers and the other little grocery stores is the only food available in the whole county.” She nodded toward Roscoe Tungate, the butcher, who’d stopped what he was doing to come listen. Everybody in the whole store had done that. “You got the only meat there is except what’s on the hoof. Ain’t right to let some folks take it all, store it up for their own selves and then there ain’t none for anybody else.”

“They paid for it,” Oscar said. “Got a right to buy however much you can carry.”

“The legal right. There’s legal and then there’s right.” She fixed him with a hostile stare. “This ain’t right.”

He took the hint.

“What are you suggesting? You sayin’ I shouldn’t sell nothing to nobody?”

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

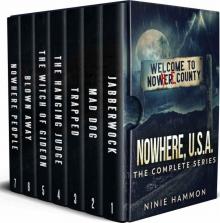

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material