- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Red Web

Red Web Read online

Red Web

Through the Canvas: Book Two

Ninie Hammon

Copyright © 2020 by Sterling & Stone

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

The authors greatly appreciate you taking the time to read our work. Please consider leaving a review wherever you bought the book, or telling your friends about it, to help us spread the word.

Thank you for supporting our work.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

The series continues…

A Special Request

Author’s Note

Also By Ninie Hammon

About the Author

Chapter One

She heard his footsteps crossing the wooden slats of the back porch and thought of horses' hooves, clattering loud and purposeful. When Brice appeared in the kitchen, his jaw was set, his eyes narrowed, the smile of greeting that bloomed on her face drained away. This was not the big man who'd volunteered to haul junk out of Bailey Donahue's attic so she could sell the not-junk at a yard sale. This was Kavanaugh County Sheriff Brice McGreggor.

"Dispatch just got a call from Corruthers Elementary School," he said as he strode past her. "A first-grader is missing."

It was his day off and he was out of uniform. He ran to his cruiser, tore out of the driveway and raced off down the street, light bar flashing and siren wailing.

Bailey felt gooseflesh break out on her arms. She stood for a long time at the door, looking at the empty place at the end of Sycamore Street where Brice's cruiser had turned and gone out of sight. She listened until the wail of his siren faded, then thought she could still hear the echo of it, but that was just in her head.

Sparky sat down in front of her in his pet-me-now pose and she reached down and absentmindedly scratched the little golden doodle behind his ears. Then she straightened and slowly climbed the stairs to the second floor. At the end of the hallway was a smaller staircase that led to the huge attic resting atop the whole length and breadth of the historic Watford House.

T.J. Hamilton was there and he spoke over his shoulder.

"Was that an ambulance sittin' in the front yard or is the house on fire?" He didn't turn around. "You ever heard of a shoebox fetish? I ain't. But somebody who lived here once musta had one 'cause I done counted thirty-seven of 'em. Think anybody'd buy a shoebox at a yard sale?"

"The siren was Brice's. There's a child missing from the elementary school."

T.J. stopped what he was doing and turned toward her, a tall, thin black man with a head of wooly hair the color of a gun barrel and red suspenders holding up his trousers.

"That all you know, a child's missin'?"

"Uh huh."

She turned away and began mindlessly stuffing a pile of tangled-up coat hangers into a junk box, trying to get her head around how horrible it must be for your child to be missing. She knew the anguish of being separated from her child, the everyday throbbing pain that sometimes reached out with a white-hot saber and seared a hole in her heart. But she knew where her child was. She knew Bethany was safe — and would remain safe as long as Bailey stayed dead. To wonder if your child was in danger, though, in pain. To wonder if someone was … hurting them … Bailey couldn't stand that.

Then she burped out a grunt of acknowledgement. Couldn't stand it — right. She'd once have said there were all manner of things she "couldn't stand." As she and Aaron drove down the rain-sodden streets toward the airport that day, she had cried out to him that she missed Bethany — the baby they had deposited in Bailey's sister's arms less than fifteen minutes before. Bailey had told him she couldn't stand to be away from Bethany for a whole week.

A whole week.

She hadn’t seen the child in twenty months, eleven days and — she looked at her watch — five hours, not that she was counting or anything. She had withstood that breath-stealing pain and loneliness, not because she was strong or brave or even stoic but because she didn’t have any choice.

"It's a little boy named Riley Campbell." T.J.'s voice startled Bailey back to the present. "A first-grader. That's what the news says." He held out his phone to her, but she didn't look.

"Says he's seven years old and that he went outside for recess but never came back in."

"He probably just wandered off, chased a butterfly or saw a rabbit. They'll find him."

Chapter Two

Brice drove 10-60, lights-and-siren, to the elementary school, and didn't stop by the station to change into his uniform. On the way, he talked to his chief deputy, Raleigh Fletcher, "Fletch," who was at the school, and got the basics of what had happened. Fletch had texted the boy's picture to every officer in the county, both on and off duty, and he gave Brice the bad news right off the top.

"The Cottonwood Festival is setting up in that field next to the school. I locked it down as soon as I got here, but it's got more leaks than a dog-chewed garden hose." Meaning there were no "entrances and exits" to close off, just a wide open area where people could come and go at will.

Brice's heart sank. The festival wasn't a surprise. He'd scheduled officers to patrol it during its weekend run. But he hadn't yet put it together that people were there now setting up, a random-grab of unvetted strangers within rock-throwing distance of an elementary school.

The festival featured dozens of booths hawking all manner of merchandise. Local artists brought their pots and paintings, added to flea market junk ranging from fake switchblades to not-so-fake nunchucks, handmade quilts and fresh-baked brownies, a petting zoo, pony rides, even a carnival.

Fletch told him that the missing child, a student in Melody McCallum's first-grade class, had last been seen on the playground during recess. But his desk remained empty after the bell rang.

Brice instructed the dispatcher to alert the sheriff's departments in the adjoining counties, a heads-up that he might be requesting assistance, depending on how things went. A clock was ticking. If the boy'd been kidnapped — and that was a call Brice was nowhere near ready to make — the first seventy-two hours was crucial. Although stranger kidnappings were very rare, statistics painted a bleak picture: sixty percent of kidnapped children who didn't survive were killed less than three hours after they were taken, eighty percent within the first two days. If

he found his fifteen-man department couldn't cover all the bases, he'd ask for help. The West Virginia Highway Patrol had already been notified.

The scene was controlled chaos when Brice arrived. There were five units from his department, plus two patrol cars from the Shadow Rock Police Department, which was manned by officers whose sole professional responsibility was writing parking tickets and being a uniformed presence outside Shadow Rock's historic homes to corral the tourists. The real law enforcement in the county was provided by Brice's sheriff's department. There was even a West Virginia State Police cruiser — Trooper Charles Richards, a man who had surely gotten all F's in the "plays well with others" column of his own elementary school report card.

Officers were posted around the perimeter of the festival beside the school, with sight-lines to each other so anyone attempting to enter or leave would be spotted. Fletch had said that two teams of officers had already searched the handful of campers, RVs and camper-trailers used by those setting up the festival — the livestock trailers that had brought the menagerie for the petting zoo and the trucks that hauled carnival equipment.

Deputy Fletcher met Brice as he stepped out of his cruiser, appearing to read from his report. In truth, Brice knew Fletch was operating on memory, an incredibly good one that took up the slack for his limited mental acuity. Reading, though, not so much.

"The K9 unit is en route. The teachers double-checked their classrooms to confirm Riley is the only missing child."

Before Fletch had a chance to continue, a car pulled up in the parking lot and three people leapt out of it, two women and a man, and rushed toward the front door of the school. Brice intercepted them.

"Are you Mr. and Mrs. Campbell?"

"Where's Riley?" cried a slender woman with red hair. The little boy in the picture Fletch had sent out had red hair. "They called and said he was missing? How can a child be missing from school?"

The second woman had her arm around the shoulder of the first. Mr. Campbell, bearded, wearing glasses, said nothing, just ignored Brice and headed into the building. Brice blocked his way.

"I'm sorry, but we have the school on lockdown right now. Nobody's going in that building and nobody's coming out of it. Please understand and let us do our jobs. Let us find Riley."

"You're telling me I can't go into my own son's school?" Fear was making the man belligerent.

"Yes sir, that's exactly what I'm telling you." Brice turned to Fletch. "If you'll take the Campbells over there …" He indicated one of a handful of benches in front of the building. "We need some information from you."

"You have to find my little boy — find him!" There was an edge of incipient hysteria in Mrs. Campbell's voice.

"The best way to help us find your son is to answer Deputy Fletcher's questions."

Fletcher took Mrs. Campbell's arm and began to guide the couple toward the table, speaking calmly.

"Ma'am, I need to know what your son was wearing when he left for school this morning."

Fletch didn't need to know any such thing. The officers had been on the scene long enough to gather all the identifying information they needed. Fletch was keeping the Campbells occupied and out of the way. He'd gather information, too, of course, find out from the couple if the boy had ever run away, if he had any favorite haunts where he might go, the names of his best friends … things like that.

Brice strode into the building and found Trooper Richards questioning the principal, Samuel Bergman.

As Brice approached, the trooper snapped his notebook shut. "That's all for now, Mr. Bergman," he said. "I'm sure I'll have more questions for you later."

Bergman turned to walk away but Brice stopped him.

"Actually, I have a few questions of my own. Will you excuse us for a moment?" He motioned and the trooper reluctantly moved a few steps away.

"Appreciate your help, Charlie." His voice was level and controlled. "But we got this."

The officer bristled. "At least I'm in uniform. And I was first on the scene—"

"I've already notified your post, confirmed that they'll dispatch detectives if I need more help." He smiled. "But we could sure use you in crowd and traffic control. The word's out and parents are—"

"I don't report to you, McGreggor." The trooper walked away and Brice turned to the principal.

"I know you've already explained what happened, but I need to hear it firsthand. His teacher was the last person, the last adult who saw Riley, right?"

"Yes, sir, Melody McCallum. And several children say … we haven't had a chance to talk to all of them—"

"Would you please get Ms. McCallum? I'd like to talk to both of you in your office in five minutes. And would you ask someone to gather up all the children who might have seen Riley today — I know there are probably a lot of them, but we need to talk to each one individually. Is there a gymnasium or auditorium where you could put them?"

"Certainly, Sheriff. I don't know what could possibly have … how … we've looked every—"

"I'm sure you have, Mr. Bergman. Your office, five minutes, okay?"

The man hurried away down the hallway.

Brice nodded at the deputy who had taken up a post at the front door of the school. Fletch had gone by the book. That was his strong suit. Almost in the manner of a savant, Raleigh Fletcher knew police procedure and protocol inside and out and was unerringly dedicated to dotting every i and crossing every t. Just don't ask him to spell a word with more syllables in it than mayonnaise. Fletch had been only a couple of blocks from the school when the 911 call came in and he'd immediately secured the building, stationing officers at all the exits. Nobody in. Nobody out. No exceptions. He had also set up a perimeter, a circle out about a hundred yards from the school where officers allowed no one in or out. When the K9 unit arrived, the dog would be taken immediately to the parking lot to inspect every vehicle. The animal wouldn't be trying to track scent in such a scent-polluted environment, but a trained dog could hear a human heartbeat in the next room with the door closed. They'd take him past every car trunk. If the kid had somehow gotten into the trunk of a car — unlikely as that was — he was in grave danger. It was a cool day for the middle of August but the temperature was eighty degrees and climbing. A child in a car trunk in that kind of heat couldn't survive more than a couple of hours — maybe less.

After the parking lot was cleared, the K9 officer would give the dog the kid's gym shoes from his locker and then walk the animal slowly around the school inside the perimeter — but outside the playground where scents would be too confusing. If a lone child walked away from the school in any direction, the dog would cross the child's path and could follow the scent from there.

The building had been divided into quadrants and four search teams were formed, each consisting of a deputy and a teacher or counselor or administrator, someone on the school staff. The teams had combed their quadrant. Then they switched quadrants and by the time Brice arrived, the whole building had been searched four times by a total of eight different people.

While he waited for the teacher and principal, Brice gave the school property a quick walk-through, not as if he expected he'd suddenly stumble upon the missing child but to refamiliarize himself with the layout of the facility. He knew every school building in the county, had been to each of them dozens of times for various reasons, in addition to taking every new officer on a schools tour, so they'd know the layout in any emergency — though that was more about responding to a school shooting or bomb threat than to a missing child.

It just happened that this building was particularly familiar to Brice. It was the building where he had gone to elementary school. The old facility had been maintained well through the years, though like every other building in the county, it had been "maintained" as it had always been rather than being renovated, or — heaven forbid! — bulldozed and a newer, more modern facility built in its place. Shadow Rock was, after all, a historic community with an economy based on tourism — on water sport

s enthusiasts at Whispering Mountain Lake and tourists who came to see the elegant homes that'd been built by the uber rich friends of Andrew Carnegie in the early 1900s. The Historical Society Nazis had done their dead level best to freeze history in the whole of Kavanaugh County, to keep every building "as-is" — even the buildings that clearly post-dated the historic homes the tourists paid to explore.

Taking long, brisk strides in the hallways, Brice could hear a murmur of voices behind the closed classroom doors, but it was subdued. The school secretary and another woman he didn't recognize in the office only nodded as he passed. They'd both been crying.

He stuck his head into the janitor's supply closet and the boiler room in the basement, and stepped out the back door at the end of the Grades K-3 hallway onto the playground. The playground equipment he remembered — monkey bars, seesaws, swings with wooden-slat seats and a merry-go-round that was already squeaking and wheezing its way around in circles when he was a boy, had fallen victim to safety restrictions. Swings had plastic seats. Everything else was stationary. He reflected that his generation had somehow managed to survive the hazards of a moving-parts playground, but quickly dismissed the mental rant he might some other time have indulged. He was just glad he wasn't a kid, grateful he wasn't a parent either.

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

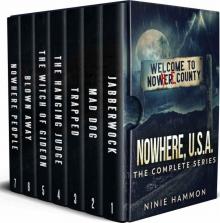

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material