- Home

- Ninie Hammon

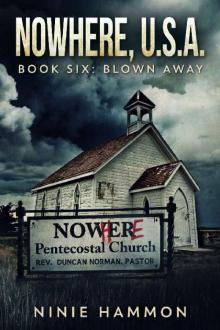

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) Read online

Blow Away

Nowhere, USA Book Six

Ninie Hammon

Copyright © 2021 by Sterling & Stone

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

The authors greatly appreciate you taking the time to read our work. Please consider leaving a review wherever you bought the book, or telling your friends about it, to help us spread the word.

Thank you for supporting our work.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

What to read next

A Note from the Author

StoryStacks Thriller Insider

About the Author

Also By Ninie Hammon

Chapter One

Neb Tackett picks up the shot glass off the bar and knocks the drink back in one swallow, wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. Lifting his boot down off the bar rail, Neb …

No, not Neb. Something else, something sexier. Tex. No, Tack! Short for Tackett. Yeah. Folks call him Tack.

Tack feels the liquid warm him throat to groin, though his groin don’t need no booze for that. Thinking ‘bout dropping a man with one shot turns him on like bedding a good woman. Tack sets the shot glass down on the bar with a clunk and casts a glance at the bartender. Whiskey Joe is slowly drying a glass — well, shining it ‘cause it’s already dry — and their eyes meet. Tack nods, barely dips his chin …

Tack’s chin has a dent in it, one of them cleft things like Kirk Douglas. And he needs a shave, too, has a day’s growth of beard on his face.

Tack turns his back on Whiskey Joe and strides across the room that smells like beer and worn leather and old sweat, his spurs making a clinking sound with every step.

Lily rushes to him, puts her hand on his arm, gently holding him back.

“Tack … please.” Her voice is deep and throaty.

No, not a deep voice. A high voice — but not squeaky. Tinkle-y. Like wind chimes, sorta.

“Don’t do it,” Lily begs and her voice sounds like little bells ringing.

Tack looks down into her big brown eyes as they fill with tears.

“It’s my job, Lily. You know that. Now step aside.”

“But they say the El Dorado Kid is lightning fast.”

Tack smiles that crooked grin of his that melts women’s hearts, reaches out and brushes a strand of Lily’s long red hair back from her face.

No, blonde hair, like May Ella Martin’s who’d lived at the bottom of the hill — the Martins who had a phone and people left messages there for the Tacketts. Him and May Ella had sex in the old chicken house behind her daddy’s barn but didn’t nobody know and then she dumped him. But Lily’s beautiful, ain’t dish-faced like May Ella Martin. Lily looks like … like … Elizabeth Taylor! Yeah, and Lily has black hair, too, just like Elizabeth Taylor’s and her eyes is violet like that.

Tack looks down into Lily’s violet eyes and says, “Then I guess I’ll have to be faster than lightning.”

She bows her head and her shoulders shake but she doesn’t cry out loud because everybody knows Tack likes his women strong.

“This won’t take long.” He brushes past her.

“I love you,” she says.

No, she doesn’t say it out loud. She whispers it, doesn’t mean for him to hear it but he does.

I love you, too, Tack thinks but doesn’t say it out loud because Tack can’t love any woman. He lives every day on the razor’s edge of danger … it wouldn’t be fair to ask a woman to share a life like that.

Pushing through the swinging doors, he steps out onto the wooden sidewalk and a little freckle-faced kid runs up to him.

“Gee, sheriff, can I see your guns?”

“Why sure you can, son.”

In a movement that’s too fast to follow, Tack crosses his arms in front and snatches the Colt .45 from his left holster with his right hand, and the one in his right holster—

“Whatcha doing, Neb?”

Zach was standing on the top step of the porch that wrapped around the back of the house. It was screened-in so’s you could sit out there at night and not get eat alive by mosquitoes. Neb fumbled and dropped one gun into the grass, hadn’t even been able to get the pistol on his right hip out of the holster at all.

“Ain’t none of your business what I’m doin’!”

Neb didn’t even look at Zach. Nebuchadnezzar Tackett was Viola’s oldest son and that meant he had ought to be respected by his younger brothers. They’d ought to listen to him and do what he told them. Well, all except Malachi and he didn’t do what anybody told him — not even Mama.

Kneeling in the grass, Neb picked up the shiny Colt .45 pistol that him, Obie and Zach had took when they broke into Lester Peetree’s hardware store last week. They stole pro’lly two dozen firearms, all kinds and sizes. Took every shell of ammunition they could find, too. Neb wasn’t rightly sure why it was Mama’d wanted all that, then figured out she didn’t want it — she just didn’t want nobody else to have it. Zach’d said he thought Mama intended to gather up all the guns in the whole county eventually, and maybe she did. Neb hoped so ‘cause then she wouldn’t never notice that he’d snatched the matching pair of .45 pistols with the pearl-handled grips and their soft leather holsters from the haul at Peetree’s, never even showed ‘em to her, kept them pistols for his own.

“Mama called from the courthouse and said for you and me to go back out to Howie Witherspoon’s place and see did him and the kid come back yet.”

They’d gone out the day before, beat on the door, looked all around but couldn’t find him — which didn’t make no sense ‘cause his car was in the driveway.

“You and Obie go. I’ll stay here with Essie.”

Esther Ruth didn’t never need nobody to stay home and babysit her until they moved out of the house in Turkey Neck Hollow and into this big place on Main Street in Persimmon Ridge. She usta stay at home all day by herself and she’d be fine, just sit in the sunshine rocking back and forth, singing her song. They’d only been here two days, though, since Mama kicked old man Nower out on Sunday, and Essie hadn’t got used to it yet, was scared to be here alone.

“Mama said for you and me to go. She told Obie to stay here and mow the grass.”

Mow the grass. Good luck with that! It was six inches tall and so thick it gummed up the mower blades. Neb had mowed part of the backyard ‘fore he give up and he had to stop every twenty feet or so to clean the clumps of wet grass out of the blades. If i

t wasn’t mow the grass, it was trim the rose bushes. They had thorns, would scratch your hands like you’d got hold of a bobcat. Sweep the porches. They hadn’t had no yard or flowers on Gizzard Ridge and if anybody’d ever swept the porch there, Neb hadn’t seen ‘em do it. But there was always some kinda job to do around the Nower House — the Tackett House. It’d took him and Zach half the afternoon yesterday to dig up that National Historic Landmark sign out of the front yard. If Mama heard Neb call it the Nower House, she’d skin him alive.

Getting to his feet, Neb fit the pistol back into the holster on his belt and when he did he seen what the problem was. You could draw both guns at the same time straight out, but if you wanted to do a cross-handed draw, you had to turn the holsters around backward on the belt. Them holsters wasn’t made to pull the guns out from the front side.

Now that he’d figured it out, he’d get it right. Just needed to practice, that’s all. He’d work on it again soon’s he got back.

“Won’t take no time at all to get there in my car,” Zach said, his chest all puffed out. He’d stole Bud Griffith’s black Corvette and woulda drove it around all day long if Mama hadn’t told him he was too old for such foolishness. Neb’d thought about picking hisself out a car but didn’t see no point in it since all the gas was gonna run out eventually. But Mama wasn’t worried about that a’tall, had some plan in mind she hadn’t told nobody about. Mama always had a plan.

“That ‘Vette’s only got seats for two people.” Neb crossed the yard to the porch. “So where was it you’s plannin’ on puttin’ the Witherspoon guy and his kid when we find ‘em?” Neb sneered. “Maybe we could tie a rope to their feet and drag ‘em.”

Zach was itching to drive that car so bad he hadn’t thought about that part. Neb shook his head. His younger brother couldn’t be trusted to put his pants on with the fly in the font, wouldn’t surprise Neb to see him walking around with the zipper up his butt.

“We’ll use Obie’s Ford.” Obie had come home last night with a black Ford pickup. Stole it from somebody but Neb didn’t know who. “Put the both of ‘em in the back like bales of hay. You get the keys while I put these away.” Neb kept the guns out of sight ‘cause Mama might see ‘em and fancy ‘em and take ‘em away from him.

The phone rang inside. Mama. When it was him and his brothers in the sheriff’s office at the courthouse — throwing darts or playing cards — and Mama was home, she’d call about every five minutes wanting something. Neb thought Mama liked having a phone right there in her own house so she made up excuses to use it. Of course, he had better sense than to say a thing like that to Mama. He wasn’t stupid!

He heard Obie talking in the den when he went upstairs to put the gun and gun belt under his bed — in a bedroom he didn’t have to share with nobody! Apparently, Mama wanted to know if him and Zach had left yet.

“They been gone about ten minutes, Mama,” he heard Obie lie, then pause. “Yes, ma’am, I’s on my way out to crank up the mower when the phone rang.”

Soon’s Obie hung up, Zach looked up at Neb coming down the stairs. “Obie won’t give me the keys.”

“I don’t like other people drivin’ my truck,” Obie whined at Neb.

“Yore truck? How you figure being selfish with a truck that don’t even b’long to you?”

“Does, too. I took it and now it’s mine. Same’s Zach’s car. Mama said for you and Zach to go find Howie so you can take Zach’s car.”

Neb sighed. The two of them sounded like little kids fighting in a sandbox. Neb started to lay down the law, but didn’t bother. They wasn’t gonna need Obie’s truck to haul Howie and his brat back into town because they wasn’t gonna find them. They’d searched the Witherspoon place top to bottom yesterday when Mama sent them looking the first time. Howie Witherspoon was long gone.

“C’mon, then,” he told Zach. “I got things to do.”

Soon’s him and Zach was done with their wild goose chase out to the Witherspoon place, Neb’d come back home and practice, would turn them holsters around backward so’s the pistols would slide out fast.

Fast as lightning.

No, faster than lightning.

Chapter Two

Charlie shot Malachi a look over Sam’s head and he nodded. The look said: I’m worried about Sam. And Sam did look terrible — well, as terrible as it was possible to look with a china-doll face and glossy red hair. As Malachi studied her profile now, with her attention focused on the little boy lying on the bed, he was reminded what a beautiful woman she was.

But right now that beautiful woman was worn out, had exhaustion — both physical and emotional — stamped on her face. Malachi was certain she had not slept a wink, had sat up in the chair beside Rusty’s bed, vigilant. Hoping, praying he would wake up. But he had not.

He glanced at Rusty, his face so still, his features outlined in the glow of the lamp on the table beside the bed. It wasn’t a hospital-room lamp. Malachi had brought it down from E.J.’s apartment upstairs because the lone pull-chain light in the middle of the ceiling in the converted stockroom provided little light and the illumination was harsh and garish, like a police lineup. The lamplight was softer, cast a warm glow on the side of the boy’s face. He seemed much younger than twelve, like a little boy fast asleep, a handsome kid, looked like his mother.

“I won’t bother to try to get you to take a break,” Charlie told Sam. “I know you won’t. But I can make toast, though it’s the outside limit of my culinary skill. I made some in E.J.’s toaster upstairs. Two heels, the last of the loaf and the bread’s stale — but you won’t taste it anyway. I brought a jar of Mama’s fruit preserves from home just to entice you.” Charlie held out a plate to Sam. “Just a couple of bites.”

Sam gave Charlie a wan smile. “I appreciate the effort but I’m not—”

“Would you take that as an answer?” Malachi said firmly. “If you had a patient who clearly needed some food in her stomach — to keep her strength up — would you let them off the hook because they weren’t hungry?” He held up his hand before she could protest more. “It is humanly possible to consume food even if you’re not hungry. Just ask any Marine grunt. At the end of a fifteen-mile hike with full pack, you think you’re too tired to eat, but if you don’t, the sergeant will stand on your chest and force the food down your throat.”

She still hesitated.

“You reeeeally don’t want me to stand on your chest and force this toast down your throat.”

She reached out and picked up a piece. Charlie’d slathered it in strawberry preserves. When she took only a small bite, Malachi scowled at her and she swallowed and took another bite, a normal one.

“The jam’s good,” she told Charlie in a voice that sounded as thin and dry as autumn leaves scraping across a sidewalk.

Rusty lay on his right side, perfectly still beneath the white sheet. Sam had wrapped the bandages she’d put on his back all the way around his chest, so he was encased in white gauze from his shoulders to his waist. They’d carried the boy into the building from the parking lot after crazy Claire McFarland had forced him to “ride the Jabberwock” with the dead body of her son — for reasons that made sense only in her twisted mind.

When they’d placed Rusty on his belly on the long metal-tray exam table and Malachi got a good look at his back, an unexpected wave of pure rage had washed over him. Claire McFarland had shot the kid! Shot him in the back with a shotgun loaded with buckshot. Malachi had coldcocked her in the parking lot and confiscated the shotgun, but when he’d seen Rusty’s back, he’d wanted to go back out to the parking lot and hit her again. Might even have done it but Raylynn said her husband had shown up and taken her home. And Lester Peetree — dependable Lester Peetree — had taken Douglas’s body back to Bascum’s Funeral Home.

While Sam and Charlie had carefully picked pieces of buckshot out of the flayed skin on the boy’s back, Malachi had gone to Martha Whittiker’s house looking to “borrow” a bed. Martha now lay with her gra

ndson in side-by-side body drawers in the basement of Bascum’s, so she wouldn’t miss it. Malachi had found a single bed with a metal frame in her spare bedroom and brought it back to the clinic to set up in the storage room Sam had turned into a hospital room for Rusty. Just down the hall in the veterinary clinic, E.J. lay in a real hospital bed. Roscoe Tungate’s late wife had ALS and he’d gotten a hospital bed and moved it into his living room so he and his daughters could care for her at home until she died. After E.J. was mauled by Judd Perkins’s rabid dog, Roscoe had hauled the bed to the veterinary clinic in the Middle of Nowhere. But if there was another hospital bed floating around somewhere in the county, Malachi didn’t know where.

Sam had bandaged Rusty and started an IV to replace the fluids oozing out of the weeping wound on his back. She was careful to move him as little as possible because the wound you could see was not nearly as threatening and terrifying as the one you couldn’t see. Blood had been seeping out of his ear and he was unconscious. They all vividly remembered what the repeat ride on the Jabberwock had done to Abby Clayton. A stroke and brain damage. And her third ride had …

Rusty still had not regained consciousness. Malachi was certain every minute that boy lay on the bed unresponsive, his mother was dying a thousand lifetimes. Sam was a good mother. Rusty was lucky to have her. And the boy was a good kid, a real good kid. If anything happened to him …

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

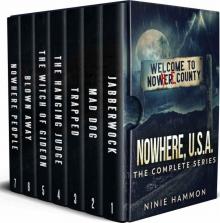

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material