- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Page 9

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Read online

Page 9

Then Harry Tungate told them his story.

Chapter Sixteen

E.J. didn’t usually make “house calls” for dogs. You could bring a dog or cat into his office — or a goat or a sheep, for that matter. But bigger farm animals, he tended to on the farm. Judd lived on Sims Lane on the other side of Hollow Tree Ridge from Route 17 South. E.J. hadn’t been out to Judd’s farm since Judd’s milk cow, a big Holstein with the most sour disposition of any cow E.J.’d ever met, was having trouble calving. He’d gone to the farm so he and Judd could pull the calf. Cows were large animals and gentle to a fault — which was a very good thing. E.J. had always thought that if they had ever sent a spy to the stockyards to see what happened to all their friends who left the farm and never returned, they could band together and do some serious damage. A Holstein weighed 1,500 to 2,000 pounds — about the size of the white rhino at the Louisville Zoo. Judd’s Clementine had tried to mash E.J. up against the wall of the stall twice before they ever got that calf out of her.

The last time he had seen Buster was for that infected toenail. Part of Raylynn’s job was to keep track of his patients’ vaccinations and send out reminders to folks when the shots came due. He hadn’t asked her, she’d been busy when he left, but he was sure she’d sent one to Judd months ago. But Judd’s wife Mildred had died a year and a half ago, and he hadn’t been firing on all cylinders in a long time.

That was part of the reason E.J. had dropped everything to go out to Judd’s — because he felt bad that they hadn’t followed up with him on Buster’s shots, knowing he was likely to forget about it.

It wasn’t like E.J. believed the dog had rabies. Just missing a booster didn’t preordain infection. There were half a dozen reasons why a dog would stop eating his kibble, but the eating rocks part was concerning. E.J. would bet the behavior was linked to Mildred’s death, and to Judd’s subsequent inattention. Eating inanimate objects was usually a sign of stress and insecurity. But the behavior itself was concerning because chewing rocks was dangerous to a dog’s mouth and teeth. Sharp edges could cut their gums and tongue, crunching could break teeth. And swallowing rocks could be deadly — an intestinal blockage or choking. It was also possible that Buster’s diet was off — that he was trying to get calcium, magnesium or some other vitamin or mineral he wasn’t getting in sufficient quantities.

Those were matters that needed to be addressed.

Killing the chicken, though … E.J. wasn’t overly concerned about that. The dog was just being a dog. Even though humans believed they could train dogs out of innate behaviors just because humans found them upsetting, the results were usually mixed. He’d have to talk to Judd about the incident — had the chicken made a sudden movement, odd sound? Or was it possible Buster was only playing and because he was so big — Lenny in Of Mice and Men, “I done a bad thing, George.”

The real bottom-line reason why E.J. was flying down Gallagher Station Road to the Perkins farm was that it was an excuse to get out of the office — a really good excuse — and he had to get out of there for a while or he would lose it in front of Sam or Raylynn or one of his “patients.”

E.J. burped out a bleat of laughter. Never in more than a decade of veterinary practice had he given a moment’s thought to his patients’ opinion of him.

Bummer that Mrs. Throckmorton’s Persian thinks I’m socially awkward.

I hate it that Billy Wainwright’s basset hound is offended by my bad breath.

The Jabberwock.

“That’s a nonsense word,” he said out loud. “The whole thing is crazy, it’s …”

Every day since the morning he had looked up to find Charlie Ryan — McClintock — in his office with a daughter in need of stitches, he had believed it would be over soon. Oh, not right away — gone in a couple of hours like other folks said it’d be. It’d take a few days, sure, maybe even a week, but eventually the crazy storm that had blown it into the county would come roaring back and blow it out again. And that’s what it had to be — a storm. Okay, not exactly a “storm,” but some weird meteorological phenomenon, something you didn’t understand, maybe something nobody would ever understand, would spend years trying to figure out, but something real, tangible, a thing that happened and then unhappened for some kind of logical reason.

Because if it wasn’t, if the Jabberwock didn’t blow into the county on the heels of the wailing wind of that crazy storm two weeks ago … what in the name of holy God was it?

E.J. turned his van, the one he’d used to take the odd assortment of humanity out to see the Jabberwock at the county line for the first time, off Gallagher Station Road and onto Sims Lane. Judd Perkins’ farm was about a mile down, on the right. He looked at his gasoline gauge. He had had the presence of mind and the forethought that most other people had not — had filled up the tanks on both his van and his car the morning after … Abby … exploded.

Like every other farm in Nowhere County, Judd’s farm was sandwiched in between mountains. His land stretched out on both sides of a nameless little creek that meandered down the hollow and his farm meandered, too. He had a small frame house that had once had beautiful roses growing along the fence that encircled the yard. The roses had been Mildred’s and E.J. wasn’t surprised to see that they hadn’t been pruned, probably needed rose food and insecticide. Without Mildred …

A gravel lane wound a quarter of a mile beside the creek to the house and E.J. pulled his van down it and into Judd’s driveway. Judd’s pickup wasn’t in sight, and then E.J. remembered that it, like so many other vehicles, had been gobbled up by the Jabberwock.

The farm buildings were behind the house in the narrow strip of flat land where Judd grew a good-sized patch of tobacco and an assortment of vegetables, and kept a small herd of beef cattle and the lone milk cow — and perhaps her calf was still around. Oh, and there were chickens — free range, which had gotten one of their number killed in the past few hours. As he recalled, there were also geese, a couple of goats because Mildred had liked to make goat cheese, and a herd of sheep that provided mutton and lamb for their table.

E.J. got out of the van and walked in the open gate, up the sidewalk to the small concrete porch. There was a grape arbor on one side of the front lawn, and an Amish stand-up swing in the shade of the oak tree in the front yard. He knocked on the door. Nobody answered. He knocked again. Judd was probably out back tending to the livestock. Or in one of the barns. E.J. stepped off the porch and went around the side of the house, expecting to see Judd out in the farmyard behind the house. He wasn’t there. Neither was Buster.

Judd was home, though. His farm truck was parked under a sycamore tree — an ancient International Harvester, the kind that looked like it was about to fall apart … and twenty years from now would still look like it was about to fall apart.

E.J. headed out across the open area in the barnyard toward the closed barn door.

Chapter Seventeen

Charlie knew why the Tungate brothers had come to the clinic to find her, Sam and Malachi to tell them what’d happened to Harry at Abner Riley’s house and to ask for their help to find him. It was because the three of them, along with Liam and E.J., had taken charge of the Middle of Nowhere on J-Day, kept the wheels on during the disaster, and she shuddered to think what it would have been like there if they hadn’t. But the fallout from that was that many nowhere people now looked to them for continuing leadership, and dealing with the ongoing disaster the Jabberwock had created would most certainly be harder than organizing teams to hose the vomit off the Dollar General Store parking lot.

Charlie volunteered to drive them to Fearsome Hollow.

“You need to know, I’ve never been to Fearsome Hollow,” she said.

“Yes, you have,” Malachi corrected.

“Okay,” she amended. “I mean I’ve never gone there on my own, on purpose.”

He looked like he was about to correct her again, but didn’t. When their eyes met for a moment, she felt the fluttering of a

memory — a campfire, laughter. The image was a moth, there and then gone again. He looked away and she got behind the wheel and checked the fuel gauge. Everybody in Nowhere County did that these days. Luckily, her mother’s car was a Honda Legend and it had had a full tank of gas when she got here and she’d driven it fewer than twenty-five miles since.

Sam stayed behind because E.J. had not yet returned from wherever he had gone running off to right before noon. Charlie pulled out of the parking lot and headed east on County Road 278 E, known to locals as simply “Lexington Road.” Fair enough. It did eventually end up there. When she glanced in the rearview mirror, the Tungate twins in the backseat looked like two halves of an Oreo cookie without the white stuff in the middle — or would have if they’d been black.

Black.

Stuart’s face washed into her mind and she was shocked by the tears that sprang instantly into her eyes.

She has never dated a black man. In actual point of fact there’d been only a handful of African Americans in all of Nowhere County when she was growing up. Stuart McClintock’s skin is a beautiful color dark, but not black-as-a-piece-of-coal dark.

She had met him in the elevator of the Hitchcock Building. They were alone, side by side, observing elevator etiquette, looking resolutely at the numbers slowly changing and not at each other. But no way could she miss how good-looking he was. His face was perfect, looked like it’d been molded from a statue in the public square in Rome. And his somewhere-way-north of six feet height made him a “presence,” even in the subdued tones of his immaculate business suit.

The doors open on his floor and in front of them is a suite of offices: Sawyer, Cohen, Hampton, Levine, Blackledge, and McClintock, Attorneys at Law.

“Is it true that the more names there are on the door of a law office, the more the attorneys charge per hour?” She can’t believe she’s said it, had thought it and out her mouth the words fell. A horrible breach of elevator decorum.

He doesn’t seem to mind, though. Smiles. A warm, friendly, disarming smile.

“Absolutely true, but it’s in descending order,” he says, his voice a pleasant baritone. “The first name gets to charge a gazillion dollars an hour, the second name only half a gazillion. I’m Stuart McClintock.” He extends his hand and she shakes it. “I get to charge a buck-two-ninety-eight.”

That’s how it starts.

After that chance encounter, Charlie goes way more than is necessary to the offices of her publisher in the Hitchcock Building, but after half a dozen visits, she gives up on ever “accidentally” running into him again.

When her phone rings a couple of weeks later, she instantly recognizes the baritone.

“Remember me, the pitiful little attorney at the end of the name game?” There was nothing either pitiful or little about Stuart McClintock. “I tracked you down through the receptionist at Hanover Publishing. She’s become my new best friend, and she could get fired for giving me your number so please take pity on her. I had to give her a coupon for full legal services for the rest of her life as a bribe.” He took a breath. “The thing is, if I got frequent flyer miles for riding up and down in an elevator hoping to run into you, I could exchange them for a ticket to Barundi. Will you have dinner with me tomorrow night?”

Light and airy and funny. That first dinner, she had been fascinated by his hands, told him he had beautiful hands, long slender fingers. She mostly knew coal miners, she said. Their hands were imbedded with a black that’d never wash off, were scarred or missing key digits.

And she’d been gratified by his response when he discovered that Charlie Ryan was the famous C.R.R. Underhill. He loved the books, didn’t care if they were for children, he’d read them all.

Oh, they dated for several months before running off to Acapulco to get married, but he had her as soon as he correctly guessed the origin of her pen name. When he did, he quoted the One Ring spiel — “three rings for the elven kings under the sky, seven for the dwarf lords in their halls of stone, nine for mortal men doomed to die, one for the Dark Lord on his dark throne in the Land of Mordor where the shadows lie.”

They finished the last part in unison. “One ring to rule them all, one ring to find them, one ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.” He’d dropped his voice then, made it deep and sinister. “In the land of Mordor where the shadows lie.”

She knew at that moment that he was the man she’d been waiting for her whole life.

“Are you alright?” Malachi was sitting in the front seat beside her and had seen the tears.

“No, not really, but I’m getting there.” She gave him a wan smile. “Okay, trying to get there.”

“I’d go down Byrne Lane, I’s you,” said Roscoe from the backseat and she obediently passed up where she’d intended to turn off onto Pebble Bottom Road. She’d forgotten that was a thing here. Since the roads meandered around the mountains, twisted and turned and tangled, getting from point A to point B involved multiple decisions about which roads to take. And people got territorial — their way to get from Bugtussle Hollow to Bennetville — by way of Bat Cave Road, Chimney Rock Pike and Elkhorn Road to County Road 278, then Barber’s Mill Road south to Cicada Springs Road — was the best way, and men would get into fist fights about it.

Pete Rutherford hadn’t really intended to start his project. It had sort of happened to him. Over the course of thirty-five years as a mailman — no a mail carrier, you wasn’t allowed to be a “man” at anything anymore — Pete had been up and down every road, lane, dirt track, cattle run, logging road and deer trail in Nowhere County. And when he’d get assigned a new route, he’d make notes for himself so’s he wouldn’t get lost. Probably weren’t half a dozen road name signs still on posts in the whole county. Most places, even the posts was gone and if there happened to be — praise God — an actual sign, it was so full of bullet holes you couldn’t read it anyway. So he had scraps of paper that said what road forked off of what other road, added in what creek was always swollen after a rain, so he wouldn’t get stuck, things like that.

After he’d retired, he had come across a box that had all them scraps of paper in them, little maps and drawings and instructions. And he’d thought maybe he’d just draw himself a map of Nower County.

That’s what it’d been in the beginning. Just a little map. The ones issued by the state only included about three roads on them, and only one — Persimmon Ridge — of the half-dozen towns. None of the smaller roads were listed on state maps. He hadn’t seen the map for 1995 yet. There’d been one in a rack at Mini Mart in Drayton County a couple of days before J-Day and he’d grabbed a copy and put it in his glove box, but hadn’t looked at it yet. Kentucky maps became “official” on June 1 of every year, which this year had happened to be two days before J-Day and he’d had way bigger fish to fry since then than look at a map that never got anything right anyway.

The project Pete had started years ago had grown over time. He’d used a piece of poster board at first, but it wouldn’t fit on just one. He eventually ended up drawing out small portions of the whole map on those. He’d been tinkering with it for a couple of years when he got the piece of canvas — like artists use to paint with oils or acrylics — only he ordered this piece special. It was ten feet across and eight feet from top to bottom. He hung it up on the wall in the living room. He moved the couch so he could get to all of it. Then he started to put the whole thing together there. Just a hobby. It was about the time he’d found out he had cancer and when he’d first started taking treatments. He hadn’t felt good enough to leave the house, so he’d spend a little time every day drawing.

Now, when he looked at it, he was kinda awed at what it had become. If you work on anything a little bit every day for years, the result is usually pretty impressive and this map was.

It had every natural and man-made anything in the whole county. It was all there, labeled in his perfect penmanship. The creeks that fed into streams, swole up into rivers in the spring

time and dried up into rock paths in the heat of summer. Every mountain, ridge, valley and hollow. The roads, of course — the names the post office had required on addressees, though the folks living on them roads might not have called them that.

From the Wiley Bridge, a historic covered bridge spanning the North Fork of the Rolling Fork River, to Route 15 which ran west of the Middle of Nowhere, connecting Drayton County in the south to Beaufort County in the north. Through Twig, where Roberta Callison ran a chicken farm, and Wiley, the home of poor old Willie Cochran, missing both thumbs from a mining accident and who was the first fatality of the Jabberwock.

Pete looked from one landmark to another.

Bugtussle Hollow, where a cave in the limestone furnished a home to the bats that kept the mosquito population in Persimmon Ridge at bay, sitting in the shadow of Bishop Mountain with its stand of shagbark hickory trees on the southern slopes that turned an impossible bright golden yellow in the fall.

Ironwood Mountain, where the Scott’s Ridge Overlook on the cliff face provided a panoramic view of the Rolling Fork River two hundred feet below.

Little McGuire Hollow, where a clan of red-headed, freckle-faced McGuires had lived for generations, and Solomon Hollow, home to Harry Tungate, Grace Tibbits and the Cawdreys, who’d given Abby Clayton a lift to the county line for her third ride on the Jabberwock.

Sugar Bowl Mountain, sitting just like a sugar bowl between Nates Creek Hollow and Harrow Woods west of Killarney cast a shadow over Turkey Neck Hollow, where the Tacketts lived high on the side of Gizzard Ridge.

And in much smaller print, Pete had put little “you are here” symbols like was on the sign in the Middle of Nowhere, and put the names of families he knew lived along the roads.

It was stunning in its detail, a work of art. And it was accurate.

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

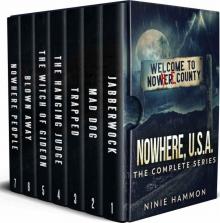

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material