- Home

- Ninie Hammon

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Page 7

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Read online

Page 7

Tears stream down Lily’s face when she figures it out. Her father left her the rocks to tell her he was still there, still alive, a message. But there is no rock today. Wasn’t one yesterday or the day before. He’d left three pieces of that geode, but not the fourth piece. An empty trail sends its own message. Her father … her mother and brothers and sisters … all the people in Gideon — they’re really not there anymore. They are gone.

Cotton sat quiet after Rose told him the story. She knew that had to be hard to put it all together in his head. She hadn’t never had to try. It was just the world she lived in.

“My friend Stuart saw someone through the mirage on the road, on the other side, but he vanished and Stuart never had a chance to talk to him.”

“Your friend seen the Jabberwock gobble that man up, watched it happen?” She could hear the awe in her own words.

“Jabberwock?” He looked surprised. “Your mother named it that, the Jabberwock, because of what Mr. Tackett said?”

“No, the Jabberwock took the name its own self.”

“How do you know that?”

“The Jabberwock told Mama.”

Cotton’s eyes turned sharp but there was no disbelief in them. “She talked to it?”

Rose nodded. “He told her things.”

“What things?”

“Just … things. Mama and the Jabberwock, they had things to say to each other after Mama done what she done.”

“What did she do?”

Rose realized she’d gone too far, said too much, so she stopped talking. Wanted the man named Cotton to go away because she was tired and her mind had got that fuzzy feeling, so she couldn’t tell if what she said was true. Like being able to fly. Like that. Might be what she’d already said wasn’t true.

It was just that she didn’t never have anybody to talk to about anything, let alone the most important thing of all.

“She done right by the Jabberwock, that’s all. That’s why it left her be. I ain’t gonna say no more.”

And she didn’t.

Chapter Fifteen

What Thelma described to them about the rocks Lily Topple found on the trail matched up like perfect puzzle pieces to what the old woman had told Charlie and Sam and Malachi.

“When we first started comparing Gideon Witch stories a couple of days ago, Sam mentioned how Liam had tossed a rock through the Jabberwock that first day to see if it’d vanish,” Charlie said. “Do you think maybe Lily’s father could see through the Jabberwock like that, maybe even see the little girl standing there on the trail?”

“I don’t believe the Jabberwock is the same now as it was a hundred years ago. It’s much bigger and stronger. That’d be the natural progression, don’t you think?”

“And you say Rose Topple called it ‘the Jabberwock’?” Sam said. “Did she tell you why?”

“She said her mother called it that because that’s what it was. She said” — Thelma paused to get it right — “‘it didn’t have no name so it took the Jabberwock for its very own.’”

“How would her mother have known that unless …?” Charlie asked.

“The Jabberwock told her. It talked to her.” Thelma held up a hand to ward off the host of questions she could see coming. “I asked about it and Rose wouldn’t say any more. Which, of course, begs a whole host of other questions — how did it talk to her? What form did the communication take? It wasn’t words on a blackboard. Even if there’d been one, Lily Topple couldn’t read.”

Charlie shook her head. Her voice was soft. “And what else did the Jabberwock tell Lily that it’d be reeeeally helpful to know right now?”

The group was quiet for a little while, each lost in their own thoughts. Then Malachi picked up the conversational ball and ran a different way with it.

“You said you’d get back to it later,” Malachi said. “I want to hear about the Quaker village that was there before Gideon.”

Charlie stopped breathing. She had been dreading this part.

“Did it … vanish, too?” she asked.

“It disappeared, but it didn’t vanish. It was wiped out by Indians and burned to the ground.”

“Well, that’s good news!” Charlie said, then looked around. “I don’t mean good news that all those people were massacred, but—”

“We get it,” Malachi said.

“There’s not much of a story to tell. Quakers were part of the westward migration through the Cumberland Gap after Thomas Walker discovered it in 1750, and apparently, a small group of them crossed the mountains and decided to stay in Fearsome Hollow, built a settlement they called Carthage by the waterfall.”

“Why?” Sam asked. “I mean, it’s a beautiful place and all, but why would you settle in mountains? The Quakers were farmers, weren’t they? Not a whole lot of tillable land in Fearsome Hollow.”

“Not now, there isn’t, but we’re talking almost two hundred years ago. Topography changes. It wasn’t a very big village, I don’t think, a handful of families with lots of kids, maybe — so there must have been enough land to grow crops to feed themselves. And remember, the woods were teeming with game. Boonesborough had been there for twenty years by 1795 and it would have been a thriving little metropolis — less than a week’s travel away.”

“Sure … just a week on horseback, right next door,” Malachi said.

“Maybe they settled in Fearsome Hollow because it was remote. The people in Boonesborough might really have been the nearest neighbors.”

“Which meant nobody saw the smoke and came running to help,” Charlie said.

“They might not have come running even if they’d seen smoke. The Quakers weren’t popular among the other settlers who branched out from Virginia. They dressed funny, held to strict moral codes about honorable behavior and honesty.”

“And that made them people you definitely wanted to avoid because …?” Sam asked.

“They had other queer ideas — you know, like God created all people equal — the radical ideology that prompted Pennsylvania Quakers to build the Underground Railroad.”

Thelma smiled.

“They didn’t lie when they told authorities there were no slaves on the premises — because in their minds, the people with black skin hiding in their root cellars were not slaves.”

“Quakers were pacifists, weren’t they?” Sam asked and Thelma nodded.

“And that would have been problematic. On the frontier, settlers had to band together to protect themselves against the Indians. The Quakers wouldn’t fight — which, I’m sure, is why the village was wiped out when the Indians attacked.”

“If the people were massacred, and the village burned down, and there weren’t any neighbors … how did you find out they were there in the first place, or what happened to them?” Malachi asked.

“I was looking up the genealogy records of the Tibbits family — traced them back to Boonesborough. Vernon Tibbits ran an inn there — but more important, his wife Naomi faithfully kept a diary!”

Charlie smiled, imagining Thelma’s face when she came upon such a treasure trove of historical information.

“An entry dated 18 June, 1820 mentioned a woman who stayed at the inn whose name was Mary Whitt.”

Thelma reached out to the pile of information she’d dumped on the table from the manila envelope and pulled from it a notebook. She flipped through the pages until she found what she was looking for.

“Naomi wrote that Mary Whitt was a white woman who’d been held captive by Indians for twenty-five years.” Thelma read from the page, “Mary was a Quaker and they built a town called Carthage beside the waterfall on Troublesome Creek. Then the Indians come, kilt the men, carried off the women, and burned everything to the ground. So the Indian raid must have been in 1795.”

“That’s all you know about Carthage?” Malachi asked.

“No. Have you ever been to Shakertown?”

Malachi and Sam shook their heads but Charlie said, “I have.”

“When I was in college a group of us went down to Pleasant Hill to eat in the restaurant.” They’d toured the grounds, too, explored dozens of preserved buildings that displayed the Shakers’ amazing craftsmanship. “I didn’t know that Shakers and Quakers were the same thing.”

“Oh, they’re not, but they’re similar.” That sent Thelma down a rabbit trail of descriptions of how the different Quaker sects developed. Thelma Jackson was the quintessential teacher.

“The Pleasant Hill Shaker Village is a National Historic Landmark. It was built in 1805, grew to a membership of three hundred people who worked 1,800 acres of land for almost half a century. That’s where I came upon the only other mention of the village wiped out in the Indian raid. I found a Bible there the Shakers called the Carthage Bible.”

The Bible was a big, leather-bound King James Bible, kept in a glass case because the pages were so fragile.

“They called it the Carthage Bible because of what was printed on the blank page in the front of the book. Under the words ‘Carthage Angels’ was a list of seventeen names. Below them were the words, ‘Please, please forgive us. Mary Whitt, 7 October, 1830.”

Thelma reached out again to the pile of information from the manila envelope and searched through it until she found a single sheet of typing paper.

“I copied the names down,” she said, holding out the sheet. “And I never found these names connected to any descendants I tried to trace, which would make sense if they were killed in a massacre.”

Sam took the sheet and began to read.

“‘Forgive us,’” Charlie mused. “That’s kind of an odd thing to say, don’t you think? Us who?”

“And why only seventeen names?” Malachi asked. “Surely there were more than seventeen people in the settlement.”

“Maybe those were the names of Mary’s children,” Charlie said.

“They had big families, but seventeen …?”

“Not just her kids,” Sam said, looking up from the sheet. “Only three of the names here are the same as hers — Jonah Whitt, Hannah Whitt and Ruth Whitt. And they could have been Mary Whitt’s brother and sisters.”

Charlie took the sheet from Sam and scanned down the names, wondering what Mary Whitt had done. What heinous sin had she committed that she was begging for forgiveness from people who’d been dead for thirty-five years?

Chapter Sixteen

Raylynn Bennett was probably the only human being in all of Nowhere County who thought the Jabberwock was the best thing that had ever happened to her.

At least she had until E.J. had gone out to Judd Perkins’s farm all by himself, which he shouldn’t have done, which she should not have let him do but she had been distracted and then … Then.

But before that, before the bottom fell out of her whole world, there had been a glorious couple of weeks where every fantasy she had ever dared to dream had come true.

The Monster was gone. Gone.

She had cried when the hope first grabbed hold of her — that if nobody could leave Nowhere County maybe nobody who was outside the county could come back, she had cried. Sobbed.

And E.J. had misunderstood.

He had found her sitting alone in the pharmacy room, perched on the stool she used to get boxes off the top shelf because she wasn’t very tall and neither was E.J. He had found her there after he’d returned from the trip out to see the Jabberwock stretched across the county line, in the van loaded with Malachi and Viola Tackett, Sam, Fish, Abby Clayton, Liam and that woman whose name was Charlie. The one E.J. looked at with the same longing in his gaze she was sure was in her own gaze when she looked at him.

He had opened the door and reached in just to flip off the light that he thought he had accidentally left on, when he saw her. Or maybe heard her.

“Raylynn?”

And she’d tried to hold it in, tried not to cry, but it was too big and she was too full, so she said nothing, just continued to sob quietly.

He had crossed the room to her, smelling vaguely of antiseptic and dog poop, which were not pleasant aromas to other people, but no one else was Raylynn Bennett.

“Hey, there. It’s okay. Whatever it is, it’ll be gone in a little while. Blew in here on a storm and it’ll blow right back out on another one. You’ll see.”

He had put his arm around her shoulders, brotherly affection, and hugged her.

She had only cried the harder because she couldn’t tell him that she wasn’t crying because she was upset by the Jabberwock. She was crying in gratitude for it. The Jabberwock was a fence. Her father was on one side of it and she was on the other. For how long, she didn’t know. But every second it lasted was a joy and wonder too big to hold inside.

He had gone to Clarksville, Indiana — on the other side of the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky — the day before, said he would stay with her older sister Eloise for the night and be back before noon.

She had gone home to the empty house that night from work at the clinic, went from room to room, screaming obscenities at him. So grateful for the solitude, the brief reprieve in her life of torment. She’d been glad of the storm that came up that night, the brief storm everybody thought had caused the Jabberwock. She’d been grateful because it had been so powerful it ripped at the shutters on the house, the ones her father had taken such care to paint and replace for the spring.

It had torn one off on the front of the house and left the other dangling. And after it was over, she’d gone out and ripped the other one off, too. Had to use the claw hammer from his toolbox to pull out the last of the screws that bound the hinge to the wall. Then she had banged the shutters against the house until they were nothing more than torn-up pieces of broken wood.

And every time she beat the shutter against the side of the house or the porch railings she imagined she was slamming it into his ugly face, breaking his nose, bursting his lip. Knocking out his teeth.

Every blow was a blow at her father. And she had slept well that night, as she only slept when he wasn’t home. When he wasn’t likely to appear in the gloom of her room, saying he “needed some loving.’”

She sometimes wondered if he had done the same with her older sister, if that’s why she had run off and got married at sixteen, had moved away to Louisville. But she had never asked, and Daddy had seen to it she didn’t have the same opportunities, scaring away anybody who took the slightest interest in her.

And there were few of those, of course.

She reached down unconsciously and pulled down the sleeve of her blouse that covered the raw red scar patches of psoriasis on her elbows. One good look at those, and the boys didn’t need her father’s threatening looks to keep their distance.

The morning after J-Day when the Jabberwock had deposited the crowd of sick people in the parking lot outside and next door in front of the Dollar General Store, Raylynn had awakened with a surge of hope that maybe, maybe, the Jabberwock was still there. Still on guard. Still keeping her safe.

And it had been.

Every Jabberwock day for a week, she had awakened in fear and only relaxed when she got to work at the clinic and saw the faces of the people for whom the fence of the Jabberwock was not the lifesaver it was to Raylynn.

As one day piled up on top of another after J-Day, she had watched in love and admiration as E.J. stepped up to the plate and did what he didn’t want to do or know how to do or was trained to do.

He’d done it anyway because that was the kind of man he was. And she had loved him more for it every day. And then Judd Perkins had called to say that something was wrong with his Great Pyrenees, Buster, and E.J. had gone to the Perkins farm to tend to the dog. The rabid dog.

E.J. had saved two little girls from certain death in the jaws of the crazed beast. Had sacrificed himself for them. And now he lay on a hospital bed in a makeshift hospital room in the clinic, with his leg a gory wound.

And the rabies virus in his veins.

When Raylynn’d heard Rusty cry out for his mother y

esterday afternoon, she’d raced from the front desk to E.J.’s room, where Rusty was trying to hold E.J.’s heaving body on the bed.

Then Sam and Malachi and the others had arrived and she’d hung back, watching in horror from the shadows. The seizure passed. When she’d asked Sam if the seizure had hurt E.J., Sam’d said it hadn’t “done any damage,” but Raylynn knew that for the evasion it was.

They’d all left then. She sat alone with E.J. as he slept. Then he came to and when he did, he’d …

He had asked her …

E.J. had been afraid he might bite her or somebody else and infect them. Then he had broken, cried, begged her not to let him die of rabies.

And she had agreed.

She had promised.

She would keep that promise.

She allowed herself the luxury of tears for a few minutes now, sitting on the closed lid of the toilet with the water running in the sink to mask the sound. Then she grabbed hold of herself and stifled the tears, stood and splashed water into her face from the full basin and didn’t even glance at her reflection in the mirror. She hadn’t been able to look at herself in the mirror, look herself in the eye, since she’d promised E.J. yesterday that she would help him die.

She had looked it up in E.J.’s textbooks the day he was bitten, had read everything she could find there about rabies.

It had been the most horrifying tour through hell she could ever have imagined. But the salient point she clung to now, that E.J. had impressed upon her repeatedly, was that the incubation time for the rabies virus could be anywhere from a week to a year! It could take months for the first symptoms to appear. But once symptoms did appear, the end was certain. After the onset of symptoms, the disease was fatal one hundred percent of the time.

The week line-in-the-sand was the jumping-off point. If the antivenom were administered within a week of the bite, before any symptoms developed, the survival rate was better than ninety percent. After that, every day was a crapshoot. Would symptoms appear today? The week was the only guaranteed safety zone, and E.J. had made her promise she would not let him suffer past a week.

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

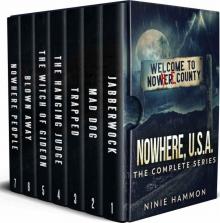

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material