- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Black Water Page 6

Black Water Read online

Page 6

“I’ve seen a lot of suicide attempts in my time,” he said, shaking his head, “but I’ve never seen one where the victim painted a picture of how she was going to look dead.”

T.J. kept his composure. Dobbs choked, but made it sound like he’d got struck by a sudden coughing fit.

Gratefully, the sheriff didn’t explain, just held out a driver’s license.

“Says here the woman’s name is Bailey Nicole Donahue. That’s not the name she gave you this afternoon, is it? You said she told you it was Cunningham, Something Cunningham, didn’t you, T.J.?”

And for a reason he couldn’t quite put his finger on, T.J. did a quick bob and weave. With his best imitation of Sparky’s pitiful look, he said, “Now, Sheriff McGreggor, for all I know she mighta told me her name was Betty Boop. My hearing’s not what it used to be.”

The sheriff barked a laugh.

“Don’t give me some ‘poor old man’ rap. Your hearing is better than mine and we both know it. Your eyesight’s probably better, too.”

“Gotta have cheaters to read with,” T.J. put in.

“Cheaters then, but not hearing aids. Why do you suppose she told you one name when her driver’s license says another?”

T.J. went with his original gut response.

“I wouldn’t make this more than it is if I’s you, Brice. It’s no big mystery. I’m sure I heard her wrong. See, I’d just gotten a good look at what she was painting and I was kinda in shock, expecting trees and flowers and butterflies and such — not cancerous tumors. You seen what she paints?”

The sheriff nodded, then commented that “all the art” he’d seen in her house had been disconcerting and let it go. Clearly, he’d seen the portrait T.J.’s mother had painted. A blind cave fish would have noticed that painting. But he said nothing about it and T.J. was more than willing to let that particular sleeping dog lie.

Chapter Six

This was nuts.

Brice McGreggor stood looking down at the still form on the bed.

It was crazy.

This was the third time he’d been here, standing like a cherry on top of a sundae, doing nothing. Wasn’t anything to do. The doctors said there was almost no chance the woman who’d put a gun to her temple and pulled the trigger would ever wake up, said they couldn’t even take the bullet out of her brain because doing so would most definitely kill her.

She was going to lie there like this, day after day. Seeing nothing. Knowing nothing.

So why did he keep coming back here day after day to watch her waste away?

That wasn’t nuts. No, that was sick.

And the reason might be worse than sick.

To be totally, brutally honest, Brice McGreggor would have to admit that the fact that she’d never open her eyes, never look up at him, was part of the attraction.

No, that wasn’t sick. That was pathetic.

He studied her, glossy black hair spread out on the pillow, a face doll-like in its perfection, unmoving. The small bandage on her right temple was little more than a Band-Aid. The bullet hole made by a Smith & Wesson Model 63 firing a .22 caliber slug wasn’t very big. Of course, she probably didn’t know, or care, what size the hole would be. Most people unfamiliar with guns think they’ll all blow a hole in you big enough to drive a road grader through. If she’d used a .44 or .357 Magnum, she would have done considerably more damage than a delicate little opening in her temple. There would have been no temple or much of a face left, in fact, and her brains would have blown out an even bigger hole in the back of her head and splattered on the wall.

Who was she, other than a name on a driver’s license: Bailey Donahue? Not the name she’d given T.J. when she met him the afternoon she shot herself. He could tell T.J. was covering for her and he couldn’t figure out why. The woman had been in town for less than a week — how could he possibly have met her and the two of them gotten so chummy that T.J. was willing to lie to the police about her?

Correction. He hadn’t lied. He just hadn’t told the whole truth. A subtle difference, but one that didn’t escape a former Chicago Police Department detective like T.J. Hamilton. He was hiding something. Brice wanted very much to know what it was, but there was no reasonable, professional reason for him to go digging around in this. Clearly, no crime had been committed. And figuring out what had driven her to the point of desperation that dying was preferable to living — or why T.J. had covered up the name discrepancy — was an exercise in futility. To what end? This case was closed. And he had plenty more that weren’t closed that needed his attention.

Still, he stood there, looking down at her.

He almost felt like he knew her, though he’d never seen her smile, didn’t even know what color her eyes were. And would never find out. That thought brought the loop full circle and he was forced to admit that was part of the motivation for returning here day after day.

She was Sleeping Beauty, with no prince to kiss her and wake her up. Which made her safe. Brice could not care about a woman. Any woman. Period. He couldn’t do that to himself and he certainly wouldn’t do it to anybody else. Brice Creighton Drummond McGreggor — his mother had been determined not to let her baby boy forget his roots — would spend the rest of his life, however brief, a loner. And no, he wasn’t gay. It wouldn’t have mattered if he had been. The same rules applied either way.

A nurse dressed in a smock spotted with — was that Shrek and Donkey? — stepped into the room and was startled to see Brice standing there beside the bed, his hat in his hand.

“Sheriff…?”

Act like you have a reason to be here!

No convenient deception leapt to mind, however, so he had to go with the truth.

“I was just checking on her,” he said, as if that were a perfectly normal, indeed a professional, explanation. “We’re still trying to track down her family, but no luck so far.”

That part, at least, was true. It was like she’d sprung up with the dandelions after a spring rain. Poof, there she was. The address on her driver’s license was … odd. It listed the Watford House’s street and number. The expiration date was 2015, so the license was brand new, which meant her previous license had obviously expired as she was about to move, so she’d put down the address of where she was moving to, not where she was moving from. Convenient timing, that. No previous address to check out. He’d run her name through a routine NCIC (National Crime Information Center) check and she came out spotless. Not so much as a speeding ticket.

There were other places he could check, other ways to back draft her life … but what for? He’d wandered through her house after the ambulance rushed her to the hospital. It had all the intimacy and personality of a room at Motel 6, where Tom Bodett always left the light on for you. Not a single photograph — family, friend, selfie. Nothing. There was only furniture enough for a handful of rooms, a bed, nightstands, dresser, kitchen table and chairs, couch and a meager assortment of other furniture, antiques he suspected had been here when she moved in. The Watford House had half a dozen bedrooms — no, more than that, but he hadn’t been counting — a parlor, library/study, family room, sunroom, den. It was huge. Why did a woman living alone need a house that big?

But to some extent, he’d figured out that minor mystery when he checked the rental listings and discovered that the description hadn’t made it clear the place was enormous, that it had once been the home of almost a dozen borders. Joe Phillips, the real estate agent, wasn’t above doing a bit of a shell game to get some unsuspecting tenant to sign a lease sight unseen. It was hard to find a tenant to rent a house like the Watford House in a town with lots of other houses just like it!

And then, of course, there was the worthy-of-an-Agatha-Christie-novel mystery he had discovered moments after he entered her house. Why had she painted a self-portrait of herself dead? Her art studio was full of organ illustrations — kidneys and hearts and other internal organs he couldn’t identify. None of them bore even the slightest resemblance to th

e stunning portrait leaned up against a chair in her living room.

What possible reason could she have had to do a thing like that?

“Maybe that’s why she did it,” the nurse offered as she hooked another bag of whatever to the line snaking down into the needle in her arm. “Maybe that’s why she tried to kill herself — because she was alone in the world.”

Then the nurse finished and paused for a moment on the opposite side of the bed. They both looked down at Bailey Donahue like she was a body in a coffin laid out for viewing. That creeped Brice out and he stepped away from the bed wordlessly and preceded the nurse out of the room and into the hall.

“The doctors think she’ll ever wake up?” Brice asked, knowing she couldn’t give him private medical information, and he’d already talked to the doctor who had admitted her anyway. But maybe things had changed.

The nurse in the Shrek smock shook her head.

“Not likely. Anything’s possible, I guess, but the safe money is on she’s going to be like that for the rest of her life … which won’t be long.”

Brice knew that a person in a PVD, persistent vegetative state, had a limited life expectancy before vital organs began to shut down. He turned in place and strode down the hallway to the elevator.

Lights through a thin slit. Each one spinning, and all of them spinning around each other. Around and around.

Her eyes weren’t open but she could still see the lights through her eyelids.

Voices. Somebody was speaking but her mind wouldn’t translate the random sounds into words.

A woman. Then a man. Then the woman again.

They were standing near her, but it sounded like their voices were coming from a long way off, down one of those long hallways in dreams where there’s a door at the end and you’re running for it but you never get any nearer. You run and run, past other closed doors, but the one at the end remains the same distance away.

And then she was getting nearer the door. The hallway was dark, but the door at the end was open a little and a sliver of light stabbed out into the darkness. And as she got closer, it got brighter and brighter in the hallway.

The voices were in the light. They were coming from the light behind that almost-closed door.

Then she stopped running, the lights and voices faded. The hallway darkened.

When she heard voices again, it was like turning the volume up on a television. They started out soft, then got louder and louder until she could tell that the people speaking were right beside her.

Jessie opened her eyes and looked up. People she didn’t know were looking down at her so she closed her eyes again.

“Miss Donahue.” A man’s voice. “Miss Donahue, can you hear me?” He asked the question with the authority of one accustomed to people responding when he spoke.

Jessie wished whoever Miss Donahue was would answer him so he’d shut up. She was dizzy and she was getting nauseated, felt like she was about to throw up. But the nausea passed as quickly as it had come, a wave receding off the beach.

“She’s coming around.”

“Amazing.”

“No telling how far back she’ll come.”

The voices receded, the bright lights behind her eyes darkened and there was cool, quiet nothingness again.

“Miss Donahue!”

“What?” Jessie tried to say, but her mouth wouldn’t work and there was some kind of plastic thing in her nose and down the back of her throat.

She opened her eyes and the world was vague, blurred around the edges like watercolors, smeared images. Then they resolved, became substance, became people.

“Miss Donahue, can you hear me?”

The man who spoke the words had dark hair and black eyebrows and his forehead was not flat but rounded, like the brain behind it was so big it was bulging out. He had a hook nose and a mustache the same color as his hair. It was thick. Jessie thought of Pancho Villa.

“Miss Donahue, I’m Dr. George Bennett. Can you understand what I’m saying?”

She tried to reach up and pull the plastic thing out of her nose so she could talk, but found she couldn’t move her arms.

The world was getting more solid now, resolving into a room and people and voices. She moved her head and the pain that shot through her skull was so excruciating she could not have cried out even if she had a voice. Even if she’d had that thing out of her nose so she could make sound. The pain blurred the world, blurred the room, muted the voices and gratefully they faded away and were gone.

It was quiet and dark when she opened her eyes. All she could see was a white rectangular shape with strips of white metal around it. She blinked.

A ceiling tile, with three brown spots on it, water spots, shaped so they looked like the face on a stick figure.

The ceiling resolved out of blur and she could see pieces of plastic tubing and could hear an annoying beep, beep, beeping sound like those machines that measured heartbeats with little dotted lines so you could see the valleys and then the mountains and then the valleys again until they suddenly stopped forming and the dots stretched out horizontally on a valley floor and the beep, beep, beep sound became a solid beeeeeeeeeeep.

That meant you were dead.

The beeping continued.

Reality began to form around her. She could feel … a bed. She was lying on a bed, which explained the view of ceiling tiles. She moved her head on the … pillow … and a thudding throb of pain coursed through her skull.

A babble of sound became a voice and words. A face appeared above her.

It was a woman. She was young, with blonde hair that she had pulled back from her face. She had on a colorful smock of some kind, decorated with … were those Winnie the Pooh characters?

“Hello, Bailey,” the woman said, in the tentative tone you used to address a person you weren’t sure spoke English.

Bailey?

“It’s good to see you awake.”

Awake. She had been asleep and now she was waking up. Waking up where?

She had annoying plastic tubes stuck up both nostrils and when she reached to swipe them away, her arms wouldn’t move. That brought the world into sharper focus. Why couldn’t she move her arms? She struggled to lift her right hand. Was she … paralyzed?

“Bailey, how do you feel?” the woman asked. Clearly, the woman was talking to her. The woman searched her face as if the answer to the how-do-you-feel question lay there and she could read it without benefit of a reply.

“My head hurts,” Jessie said. The woman’s face brightened in surprise and something resembling alarm. Maybe she really did think Jessie couldn’t speak English. “And I’m thirsty, my mouth’s dry.” She turned her head slightly to take in more than the woman looming over her and pain lumbered through her head again, a behemoth with big feet, and her world quaked with each step.

The woman picked up something Jessie couldn’t see and brought it to her mouth. A microphone with a thick cord. No, some kind of remote control. “Page Dr. Bennett,” the woman said into the microphone. “Stat.”

This was a hospital.

Jessie was lying on a bed in a hospital. She had … she didn’t know why she was here. Thoughts were hard to find. Words were harder. Something had happened and she was injured somehow. A wreck, maybe. Where was Aaron? Sudden fear pumped adrenaline into her veins and everything became instantly clearer and brighter.

“Bethany? Is Bethany alright? Where’s Bethany?”

“Everything’s fine. Just stay calm.”

Oh, how Jessie hated it when people told her to stay calm.

“I want Bethany. Where is she?” Jessie was shouting now and she didn’t know how her voice had gone from hoarse and raw to usable, but it had and she was using it.

The woman reached up and fiddled with something on the plastic tubing Jessie could see out the corner of her eye and the world instantly blurred. No sharp edges. Everything wrapped in cotton. The room grew dark and Jessie couldn’t find the strength to s

ay anything else. But that didn’t matter because she didn’t know what she wanted to say, anyway.

Chapter Seven

The next time Jessie came back to the world, she kept her eyes shut, pretended to be asleep, afraid if the nurses knew she was awake, they’d turn that little dial on her IV line and zap her back to LaLa Land.

She lay in the bed, listening to hospital noises, trying to piece together what had happened. Given the pain movement planted between her ears — not the saber stab of agony that was a ghost in her mind, but a thudding, pounding presence — made it clear something was wrong with her head.

Duh.

She tried to remember how she got the head injury.

Her thoughts didn’t feel right in her mind, things that ought to make sense didn’t. It didn’t seem to her like she had lost any thoughts, any memories. But then if she had, how would she know? She believed everything was still there, only not arranged in the order it had been before. She could find a thought if she looked for it, but she had to dig. All sixty-four of the crayons in the giant economy box had been dumped out on the floor, mixed up. Coloring a picture required digging around through the pile, searching for the shade you needed.

Understanding dawned on her slowly, not some dramatic memory, but little memories tiptoeing into her mind as silent as mice in house shoes. Fear for Bethany and Aaron faded away and was replaced by a bleak sadness that hurt way more than the injury to her head. She didn’t have to worry that they had been in some kind of accident with her and even now lay in an adjacent hospital room fighting for their lives.

She knew what had happened to Aaron, and was profoundly grateful that the quality of her remembering apparatus made it impossible to process those images, made it easier for her to dodge away from that place, that time, duck, so the agony of it missed her, flew over her head so close it ruffled her hair.

And she knew why Bethany was not here with her.

She remembered a kitchen in a house somewhere, a gun … and an old man with a painting of her with a hole in her head, but she must have dreamed that part.

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

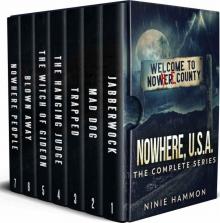

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material