- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Red Web Page 5

Red Web Read online

Page 5

A picture rested on the easel set in the middle of the room's perfect northern light. No work of great art with emotional power and psychological punch. Just a colored illustration.

"It's a gall bladder." She held up a medical textbook with a photograph of an actual gall bladder, moved the gall bladder painting off the easel and set it in front of the window to dry.

"How do you plan to replicate a process you don't understand?" Brice asked.

"I have no idea." She went to the far side of the room where several blank canvasses were leaned against the wall, selected a large one, maybe three feet square. "T.J.’s mother didn't know why it happened to her, or how the process worked — or if she did, she never told T.J. And she painted — what? — dozens of paintings. It's only happened to me once so I'm certainly no expert."

She set the canvas on the easel.

"All I could think was that when I touched the Adirondack chair, I was 'connected' to Macy Cosgrove — after I'd painted her portrait. So even if the painting's no help, maybe I'll connect …"

Brice pulled the baggie out of his pocket and handed it to her.

"Riley's teacher gave this to me."

Bailey opened the baggie, took out the picture and stared at it. The photo in the newspaper had been Riley's school picture. This was a snapshot of a red-haired little boy with a crooked grin, holding up a finger painting with hands still covered in paint. She studied it. Then she set the picture aside and picked up a paintbrush, dabbed it in white paint. She cast a single sideways glance at Brice. His face was stern. Then she touched the brush to the canvas.

Chapter Seven

Bailey's studio vanished in an eye blink the instant she touched the paintbrush to the canvas.

Static. Music. More static. Then a male voice warbles, "… takes my breath away, the way you look tonight …"

"Oh, wait — stop there, turn it up," a woman says. "I love Elton John."

The music plays louder, but the sound's muffled coming out the speaker of the baby monitor lying beside the little girl. But Mommy wouldn't allow her to ride in the camper hooked to the back of their car unless Daddy figured out a way for them to talk. He said muffled was better than nothing.

The little girl lies on her back on the camper seat and watches the world fly past the porthole in her castle. Castles in stories have names, but she can't call her castle "Burro," which is the name on the outside of the little camper. That's a dumb name for a castle.

The as-yet-unnamed castle — so tiny, like a dollhouse — is the best birthday present she ever got, only it's not really her present. It's just borrowed. But for now, she pretends it belongs to her.

She sucks her thumb happily, with her index finger hooked over her nose. Mommy and Daddy say she's way too old to suck her thumb and they don't like it, especially Daddy. He says if she keeps doing it she will mess up her front teeth and he'll have to pay for something called "braces." She likes riding back here in the camper so she can suck her thumb and they can't see.

The green of the passing trees smears the gray clouds. The sky is all one color. Not blue with white clouds that look like cotton candy, but solid gray. It looks like one of those smooth rocks she finds in the creek that runs behind her great aunt's house, where she's not supposed to play because she'll get dirty and her aunt doesn't like for her to get dirty. She plays there anyway, sneaks out of the yard, but she's careful, takes her shoes and socks off and leaves them on the rocks beside the creek. The rocks that are the same color as this sky.

She wonders what the sky is made of. Is it a rock, only a great big one, so big you can't see the edges of it? If it's a rock, what holds it up there? Can it fall down, maybe, if whatever is holding it — like tape or glue or something, lets go? Even Superglue lets go sometimes. Daddy glued the broken horn back on her unicorn with Superglue but it came off again anyway so maybe the rock sky could come off and drop on the world and crush it.

She takes her thumb out of her mouth, leans over and speaks into the baby monitor.

"Mommy, if the sky fell down would it smash us?"

Mommy isn't listening. She's singing along with the song on the radio.

"… in the moonlight you just shine like a beacon on the bay …"

"He just released that song," Daddy says. "How do you already know all the words?"

The little girl asks the question again and she hears her mother's muffled voice through the speaker.

"No, Katydid, the sky isn't going to fall down." Mommy and Daddy call her Katydid. Nobody else does. She likes the name because katydids are a kind of cricket and they make pretty sounds at night. Then she hears Mommy tell Daddy, "A child who thinks the sky could fall down is too young for this."

"Oh, come on. We've already—"

"You're telling yourself she's old enough but you know better."

"You agreed that—"

"I did not agree. I just gave in. It's not safe for her to ride back there."

Mommy and Daddy had an argument about that when she begged Mommy to let her ride in the castle instead of in the car. Daddy won the argument, but Mommy stayed mad about it, even after Daddy rigged up the old baby monitor so they could talk.

"Oh, that. I thought you were talking about the whole trip, and you did sign off on that."

"In principle, yes. But I didn't know you'd come home two days later with a camper."

"I didn't start this — you did. I wasn't the one who read that every family should go camping together even if all they've ever done is roast marshmallows in the back yard."

"That's what I mean. In principle, I believe that, but—"

"Oh, the trip will be a disaster, you said, but years later, everyone will talk about the time Daddy got tangled up in the tent cord and—"

"Family bonding will cancel out the chigger bites, right, but—"

"Borrowed camper equals no chigger bites. Well, not as many chigger bites, but definitely no tent to assemble. It lets us ease into the camping experience."

"I had in mind easing into the camping experience with sleeping bags in the back yard! And on her …" She spells a word the little girl doesn't know. "B-I-R-T-H-D-A-Y."

"You packed the P-R-E-S-E-N-T, didn't you?"

"Of course, I did. Don't change the subject. A wilderness area isn't a back yard. There could be, oh, I don't know—"

"Bigfoot?"

"I'm serious, who knows …"

"Afraid the forest meanies will mistake us for sardines, jammed into that little silver box?"

They keep talking but she isn't listening because she's trying to figure out how not to get crushed when the sky falls down. She's sure the glue's not going to hold it where it is forever. Should she crawl under her bed or—?

Her mother screams, "Look out!"

There is a terrible whump sound and the castle jerks violently sideways, throwing her off the cushioned seat onto the floor. Her mother keeps screaming and everything starts spinning. The camper tumbles like a carnival ride. Her mother's screaming is cut off and everything goes black.

Bailey blinked, smelled Brice's aftershave and felt his hands on her shoulders. She became aware of her own body then, standing, leaning with her back against him. He wasn't holding her upright, just steadying her.

"Bailey?"

She relaxed her arms and heard a clatter, opened her eyes and saw a completed portrait on the easel in front of her. The clatter was the brushes dropping out of her hands onto the floor.

Two brushes.

It was all crazy, everything about it — unbelievable. But for some reason, out of all the things that couldn't possibly happen but did, the fact that she could paint a portrait with both hands was the most singularly amazing.

"Bailey, can you hear me?"

She didn't respond because the air to form words was stolen from her lungs by the image on the canvas, the paint wet and shiny.

It was fundamentally what she expected to see — a still life. The painting T.J.'s mother had painted of her w

ith a bullet hole in her temple had featured a table with a bowl of fruit. In the one she'd painted of Macy Cosgrove, there was a vase of daisies instead of fruit. This one had a bouquet of roses. But in all three pictures, the still life was just suggested, inconsequential. The focus of the work of art was the oversized, out-of-proportion window behind the table and flowers or fruit. A face had taken up the whole window in the one T.J.'s mother had painted. Her face. Macy Cosgrove, lying on her back in black mud, her whole body slathered in goo, had been in the window she'd painted. Bailey expected, hoped, to see in the window of this painting Riley Campbell — still alive. That's not what she saw.

The image in the window was not a little boy with curly red hair and serious eyes. It was a little girl with long hair in braids, so pale blonde it was almost white. Only her body from the waist up was visible. There was a huge lump on her forehead, greenish purple, and red splotches on her left cheek, at the base of her right thumb and on both arms. Bailey thought of the mosquito bite shown on her own forehead in the portrait T.J.'s mother had painted, and these splotches looked like that. Bigger, though, brighter red. Stings, not mosquito bites. Her face and hands were dirty. What Bailey could see of the Buzz Lightyear t-shirt she was wearing was stained and wrinkled. She wore little-girl jewelry, bracelets — stretchy bands with colored plastic beads, a locket, and earrings in the shape of tiny yellow flowers.

The little girl's eyes were the color of a robin's egg. A striking pale blue. Staring. Sightless. Dead blue eyes.

"Who is this little girl?" Brice asked. "And why didn't you—?"

"I don't know and I don't know. But this little girl wasn't kidnapped … or murdered. She died in a car accident."

Bailey turned out of his grasp, away from the still-wet portrait, didn't want to stand there gawking at it, hooked to it, staring. She headed toward the kitchen. "I need coffee."

Seated a few minutes later at the table that looked out over the immense back yard of the Watford House, where huge oak, walnut and maple trees painted dappled puddles of shade on the grass, Bailey idly stirred her coffee. Just habit. There was nothing in the coffee to stir. She had once in another life — literally in another life — taken her coffee so full of cream it was the color of khaki pants. Now, she took it black. And not because she wanted to be different, to remove herself from the small things that connected her to that life and that time. She genuinely preferred it black now, hadn't just made some decision to cultivate the taste. That was one of a host of small things that had just … changed after she woke up in the hospital with Oscar in her brain, the bullet that could drop her in her tracks if she banged her head on a door frame, or sneezed too violently. Maybe it was the presence of the foreign object. Obviously, brain cells had been destroyed by the bullet plowing through tissue and maybe that had changed her. Or maybe she was a totally different person now than she had been in her other life — changed by circumstance, by growing and having to become someone she'd never expected she'd be.

Not only did she drink black coffee, but she loathed onions when once she'd smothered her hamburgers with them. She'd once loved beets, couldn't stand guacamole. It was the other way around now. She had always run, but now it was no longer the natural activity of a former athlete. Now, she hated every step. Now, it was a self-discipline, a defiant "I hate this but I am by golly going to do it anyway!" She didn't care about fashion, though she'd been something of a — what was it her sister, María, had called her? — a "coat hanger" before. Now, t-shirts and jeans and running shoes were her normal attire, her black hair pulled back in a ponytail instead of coiffed in the latest style.

She really was an entirely different person.

"What happened to that little girl?" Brice asked.

"I'm not sure exactly, but I think maybe her father hit a deer. She was in a camper, apparently a very small one, pulled behind the car. Talked to her parents through a baby monitor. Then the car wrecked, rolled and she was killed. Maybe they all were, the whole family."

"So I give you the picture of a little boy who's been kidnapped and you paint the picture of a girl killed in a wreck."

"I don't think this is a what-hasn't-happened-yet picture, either." Bailey spilled a drip of coffee on the table, plucked a paper napkin from the holder and blotted it up. "I think this happened a long time ago."

"T.J.'s mother never painted things in the past, did she? I never heard him say she did. Why do you think—"

"Because I don't feel any connection to this little girl — Katydid. That's what her mother called her. It's like I'm holding the phone but there's nobody on the other end of the line. Macy Cosgrove … as soon as I painted her, I felt her. She was there, alive. The little girl in this painting isn't."

"T.J.'s mother felt no connection to you when she painted your portrait because you hadn't been born. Think maybe this little girl is so far out in the future—"

"No, her parents were listening to a radio, not an iPod or a playlist on their phone. I heard her father surfing stations. Then his wife told him to stop, she wanted to hear Elton John. It was ‘Something About the Way You Look Tonight.’"

"Maybe they were tuned in to an oldies station."

Unconsciously, Bailey began to fold the damp napkin into smaller and smaller squares.

"No, her father was surprised she knew the lyrics because it'd just been released."

Brice pulled out his phone and punched the Google app.

"The album came out in January, 1997. So you think this car accident happened in 1997, eighteen years ago?"

"What else could it mean?"

"The little girl looks like she was about the same age as Riley Campbell, a first-grader, about seven. So why did you paint a portrait of a first-grade girl killed in a car wreck eighteen years ago instead of a first-grade boy missing in 2015?"

"I have no idea." She paused, thought for a moment. "Maybe it's because I 'tried' to paint this picture, wasn't compelled to. Maybe the whole process—" She stopped and barked out a sardonic laugh. "Right, like we understand the 'process" of going into some kind of trance and painting a portrait with both hands."

"There is some kind of process involved, though, even if we don't know what it is. And maybe when you tinker around with the process, all bets are off."

"Maybe that's it. Still, it just … feels like there's some connection between the children." She noticed the tiny square of damp napkin in her hand and got up to put it in the trash. "If we knew the identity of the little girl, maybe we could find it."

Brice set his empty to-go coffee mug on the table and started to put his cellphone in his pocket, but it rang in his hand.

When he answered it, the look on his face told Bailey something bad had happened.

Chapter Eight

Caller ID on Brice's phone identified Deputy Fletcher.

"Folks in town have started listening to police scanners and a bunch of them know the codes so I didn't want to send out a 10-26."

Brice's heart leapt into a gallop and the solid ball of lead in his belly swelled to take up his whole midsection, fit so tight his diaphragm hardly had space to take a breath. Fletcher filled him in on the call the 911 dispatcher had just received.

"What?" Bailey asked as soon as he hung up.

"We got a sex offender in the wind." He dropped the phone into his pocket and got to his feet.

"Sex offender. Why would you go looking …?"

"The sex offender registry's full of child predators."

Every state required offenders to register. All 850,000 names were viewable online. Most states required them to appear in person at regular intervals to local law enforcement.

"We just got a call claiming there's an offender in Shadow Rock who's not registered here."

"What does that have to do—?"

"He was one of the carpenters working on the Cottonwood Festival grandstands yesterday."

Brice pulled out of Bailey's driveway and flipped on his lights and siren. When he got to the court

house, he met Agent Nakamura coming down the broad front steps with agents Hardesty and Gascoyne. Nakamura hadn't informed him about the lead. Intended exclusion? Or did he assume Brice would be notified because the call had come in to the sheriff's department dispatcher?

"You got here fast," was all he said.

"In this town, you can get anywhere fast."

"All right, bring a couple of deputies, then. We have an address — what do you know about 3496 Beech Grove —?"

Brice stopped in front of Nakamura.

"I need to make the initial contact."

Gascoyne bristled. "Take care of traffic control, Sheriff, and we'll handle—"

Brice ignored him, spoke to Nakamura.

"You want to question this guy or spook him so he runs?"

Nakamura stopped and looked at Brice, saying nothing in a blank-faced, definite way.

"Samuel Kent's married, did you know that?" As he drove to the courthouse, Brice had called Ancil Spencer, a man who owned a lot of low-end rental property in and around Beech Grove Hollow, asked if anybody named Kent was one of his tenants. "Wife's name is Marcy. She works at Best Buy Supermarket as a checker but she called in sick today."

That stopped Nakamura cold.

"I buy my groceries at Best Buy. She knows who I am."

"What's your point, McGreggor?"

"FBI shows up on your porch — flashing guns and badges — scared people do dumb things. But just one guy, a familiar face you've seen around, maybe not so much."

He looked deep into Nakamura's eyes.

"And what I 'know about the address' is that it's at the very end of Beech Grove Road where it cuts back into the mountain. That hollow's barely wide enough for a house, the road, a creek and a prayer. I know the mountains around there and if this guy's a hunter, so does he. He runs and gets loose in those woods — you'll need an army to flush him out."

"And you're suggesting?"

"There's an old logging road half a mile this side of the end of Beech Grove. Stop there, let out two of my deputies who'll go up and over the ridge and come down in the woods behind the house. He bails, we got him. Everybody else stay out of sight."

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

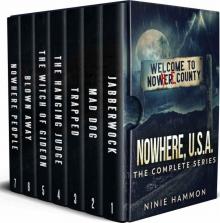

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material