- Home

- Ninie Hammon

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Page 3

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Read online

Page 3

There was a fly in the buttermilk of her decision to write, however. A pretty significant fly. More like a hummingbird. She didn’t have a typewriter. She assumed her mother still had the old manual typewriter she’d learned to use as a teenager, which had a certain appeal. There was something about that grand physical flourish of reaching up and throwing the carriage at the end of a line that was emotionally and psychologically appealing.

She had, of course, used an electric typewriter to write her first couple of books, and hitting the return/enter key carried its own danger — no one would ever know how many cups of coffee went flying when the carriage on her electric typewriter went shooting back to the right — the ruined manuscripts, the shattered vases.

But she had searched her mother’s house and couldn’t find the old manual typewriter anywhere. She’d seen a typewriter in E.J.’s office she bet she could talk him out of. Then she’d found the unopened pack of ten legal pads in the closet under the stairs and thought — why not? Tennessee Williams had written every word of his glorious plays — Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Streetcar Named Desire — in longhand. She recalled a quote from one of her favorite British authors, Fay Weldon, about a “mystical connection between the brain and the actual act of writing in longhand.”

Charlie decided to give it a shot. If it didn’t work out, she’d have a talk with E.J.

She needed an office, too, and she certainly wouldn’t be using her mother’s sewing room for its intended purpose. She just had to get rid of all the sewing paraphernalia, haul it up to the attic. Pens and pencils? The junk drawer in the kitchen. When she went there to start digging through it, her mother’s blackboard caught her eye and she stopped digging and looked at it. It hung on the wall beside the calendar next to the refrigerator and she stepped in front of it, put out her hand and almost touched what was written in the upper left corner in chalk. Get bird seed. Just those three words. Her mother’d jotted them down on her ToDo blackboard … sometime.

Charlie had gotten seed. Had scattered it beneath the kitchen window where her mother liked to stand and watch the birds while she washed dishes. But she hadn’t erased the words, would never erase them. They were a connection to her mother she couldn’t explain. Like the blackboard opened up a portal somehow that Charlie didn’t want to close.

Chapter Five

Grace Tibbits itched all over, itched in places it wasn’t humanly possible to itch — like under your fingernails. It took all the willpower she had not to scratch. She didn’t want Reece and the others to see her do that because they’d know what it meant. And it wouldn’t do any good if she took a garden claw — and that’s what she felt like doing — and raked it up and down her back. The itching wasn’t on the skin. It was under the skin. And all the scratching in the world wouldn’t make it any better. It’d just make her skin raw, so then the bottom side of her skin would be itching and the top side would be raw and that sounded like something that could ruin your whole day.

“You want something to drink, Mama?” Reece asked. And she knew why he was asking. She knew he was keeping track of how many times she got up to go pee. What he didn’t know was she threw in another time or two here and there that weren’t real, said she was going but just went into the bathroom and closed the door, stood there for a little bit, then flushed the toilet and washed her hands and came back out.

The itching was because toxins were building up in her body. Because her kidneys — little shriveled up things that they were, couldn’t clean her blood. Hadn’t been able to for more than two years now. She went twice a week to the hospital in Carlisle for dialysis. Well, she did back when it was possible to cross the Beaufort County line without engaging in an entertaining round of projectile vomiting in a parking lot bus shelter.

And as awful things went, projectile vomiting was about as bad—

No, it wasn’t as bad as it could get. Blowing up like there was a hand grenade in your chest — that was worse.

Poor Abby Clayton. That child was dumb as a shovel but she did love that little baby something fierce and she would have done anything to get to him. Including blasting body parts and gray matter all over the Dollar Store parking lot. Grace was grateful she hadn’t been there to see it happen. She had left before Abby came back that last time. And she’d told her oldest son, Reece, “The shape that poor girl was in after the second time, it’s not hard to believe that one more pass and her body’d bust open like a pimple.”

“Mama!” he’d said, horrified.

She did a lot of that — horrified her children. They’d decided their own selves what their mother’d ought to be — based on what she never did figure out. But it was an idealized version of motherhood, like those “Breck” girls on the outside of the hair color boxes in the 60s — all perfect. Maybe they’d got their image from hair color boxes or television or some book somewhere or just made it up in their own heads. Grace never did know, but she did know she never had come close to that image. Just for fun, she’d once put on a fake pearl necklace to do the dishes, hoping they’d get the Leave it to Beaver reference, but it blew right past them.

She’d asked Reece to bring her into E.J.’s clinic today to see Sam, didn’t want to do their regular home visit because she wanted to talk privately with Sam. She needed somebody to be real with and if there was anybody for that job it was Sam Sheridan. And maybe she could get Sam to have a talk with Reece. He was the worst. The girls, Audrey and Mary Jo, just gave her miserable looks and thought of something they had to do in another room — like she was already dead and not just on the way. And Oliver wasn’t here. He’d gone to spend the weekend with his girlfriend in Ashland — he didn’t think she knew that part — so he’d missed the whole show.

She hated that. She would have liked to have had a chance to tell her youngest son goodbye.

Raylynn Bennett looked up and called out “Grace Tibbits” and Reece stood up like a jack-in-the-box, powdering sawdust off his coveralls to the floor. He was a carpenter, wearing his customary work clothes — overalls over a white tee shirt — and should have dusted off the sawdust before he came in. These days, he was too distracted to think about being polite.

“I am fully capable of doing this all by myself.”

“I want to be there for you.”

“You have been, and don’t think I don’t appreciate it. But I am seventy-nine years old and I really am ready to cross the street by myself.”

“This isn’t a joke, Mama.”

“It is if I say it is. Goodness, boy, you get your panties in a wad every time I fart. I promise on the soul of your poor dead father” — a carousing drunk who’d bailed out on the family while the kids were still young enough to believe the tale she’d made up about him being killed at sea — “that I will not drop dead between here and the examining room. I can guarantee that much. Beyond that, all bets are off.”

She leaned on her cane when she walked. She hated that, but she supposed it was better than face-planting on the floor and she had gotten very weak. On J-Day, after she’d gotten her fire-hydrant nose bleed under control, she’d been strong enough to stay around and help with the “wounded.” She’d been up squirting puke off the parking lot while Reece was still too sick to do anything but groan. She barely had the strength to walk now, though. Dead kidneys would do that to you.

Raylynn opened the examining room door and Sam looked up from jotting something on a chart and burst into the smile that planted a dimple in her right cheek. Why couldn’t Reece have found a girl like Sam instead of that insipid little church mouse, Cissy, who was afraid of her own shadow? Of course, Sam would have been strictly off limits. More important than the fact that she was twenty years too young, she was over six feet tall. Poor Reece had topped out at five feet eight inches and that boy’s ego was far too fragile to survive looking up at the woman on his arm.

“Grace! How are you?” she said in that husky voice of hers.

The veterinary clinic had been transformed in

to a medical facility in the two weeks since J-Day. She didn’t know who exactly had done it, but if she was to guess she’d say Charlie whateverherlastnamewasnow, Liam, E.J., maybe even Malachi Tackett — which was a wonder Grace would dearly love to live long enough to see unfold. She’d glanced into the five transformed exam rooms as she hobbled down the hallway. Exam Room 1 on the end was the biggest, with several small exam tables and wire kennels of all sizes. Double doors in the back of the room led to the hallway of the animal hospital with “hospital” rooms and kennels on both sides where litters of unwanted kittens and puppies meowed and yapped alongside recovering animals — a goat with a broken leg, a sheep with an infected eye and pets in all shapes and sizes.

Sam had on the white lab coat she always wore on her home visits. She’d confided to Grace that wearing it was kinda playing make believe for her, pretending to be a doctor, and now … well, she and E.J. provided the only medical care available for the … however many people it was who lived in the county.

That’d been discussed more in the past two weeks than in all the seven-plus decades Grace Tibbits had lived here. It’d suddenly seemed important to know how many people lived in and were now stuck in Nowhere County. Who knew? Until two weeks ago nobody cared.

They — whoever “they” were — had gone to considerable trouble to make this vet clinic a facility for humans. It was certainly big enough, might be the only thriving commercial concern in the whole county. E.J. had patients in all the surrounding counties, looked after thoroughbreds on horse farms as far away as Lexington.

But some things weren’t changeable. No comfortable examination table, just metal, more like a big tray in case a dog-patient decided to take a leak. Grace could have tried to haul her butt up onto the metal tray/examining table, she supposed, but they really didn’t have to worry that she was going to pee anywhere. Peeing was a skill Grace Tibbits was quickly losing.

“How about we cut to the chase,” Grace said, and saw the smile settle into Sam’s face but not fall off. It was real.

“I’d bend over and show you but you can see for yourself. I’m starting to swell up like a toad.” She didn’t make any reference to how Abby Clayton’s looked when she appeared in the Middle of Nowhere that last time but they were both thinking about it. “That’d be fluid retention.”

Grace ticked the symptoms off on her fingers.

“Itchiness, check. Shortness of breath, check. Fatigue — I’m so tired it makes me tired to think about being tired. Weakness. I don’t know why they list that as a separate symptom because it’s the same thing as fatigue. Irregular heartbeat, check. I don’t yet have confusion, or if I do I’m too confused to know it. Nausea, not yet, thank you, Jesus. And …” She paused, looked directly into Sam’s blue eyes. “And the seizures, coma and death parts are, I am sure, coming soon to a kidney-free person near me.”

Sam said nothing, just reached out and took her hand.

“I’m dying. I know it. You know it. My kids know it. But they refuse to accept it. What they don’t get is I need them to come back to reality out of la-la land because … I want to say goodbye. How can I do that as long as they’re still pretending everything’s fine, Mama, you’ll be better tomorrow, you’ll see.”

When Grace saw the tears appear in Sam’s eyes and slide down her cheeks, she thought to herself: Why couldn’t Reece have married Sam Sheridan?

“It’s Reece I’m worried about. He gets wound tighter and tighter every day, desperate to find some way to help. I don’t want to sound like a harbinger of doom, but that boy’s liable to do something absolutely crazy.”

Chapter Six

After determining that there were, indeed, all manner of writing instruments in the kitchen junk drawer — pens, pencils, Sharpies, Magic Markers — Charlie called out, “Merrie, where are you?”

She hated the anxiety she always heard in her voice when she called out to the child, which, of course meant the child wasn’t within sight and Charlie’s gut yanked into a knot whenever she couldn’t look at her little girl. See her. Reach out and touch her. Even when she could hear the sounds of her playing in the next room, Charlie felt anxious and uneasy. She had paid dearly for the privilege of overprotecting her three-year-old. Still, she hoped it would ease off because it wasn’t good for Merrie, or for her either. Charlie would work on it. But not today.

“Here, Mommy,” piped a voice from the living room, where Merrie had spent the better part of the morning taking the cushions off all the furniture and stacking them on the floor, and trying to drape blankets over them to make a tent so she could camp out.

“Come on up into the attic with me.”

“I busy.”

“Get un-busy.”

“I making a town.”

“Good, if there’s anything Nowhere County needs it’s a new town, but you can finish it later.”

“I don’t wanna come.”

Charlie bit back her response. She had to return to the mother/daughter relationship she’d had before the nightmare eternity when she’d believed the little girl was dead. This pleading, begging tone she heard in her own voice when she told the child to do something was unhealthy. Had to fix it.

“You don’t have to want to come. But you do have to come.” She paused for a beat. “Now.”

The little girl emerged from the living room and the sunlight streaming through the doorway lit up her face and Charlie almost gasped from how beautiful she was. Oh sure, all mothers thought theirs were the most beautiful children who ever drew breath, but Merrie … Her eyes were show-stoppers, blue like Charlie’s, but a shade lighter — the color of a robin’s egg or the sky on a summer afternoon. Set against her olive skin they were arresting, seemed to glow like blue jewels inside a fan of long, black lashes. And the shiny black curls and full lips that were her heritage from her father’s side of the family … she was gorgeous.

“I wanna play in my fort.” She stuck out her lip in a pout.

“Don’t you want to climb a ladder?” Taking her hand, Charlie led her into the hallway, reached up and grasped the dangling fob that pulled down the retractable folding attic stairs. She lifted Merrie to the ladder.

“We’re going up into the top part of the castle, where we can look out the window and see the whole kingdom.”

“An I’m a princess!” Merrie was instantly into the fantasy. Clearly, imagination was as hereditary as her beauty. “You get to be the … the lady who milks the cows.”

There was surprisingly good light in the attic, with windows at both ends on the dormer and three lights on wires with pull chains. Charlie pulled the ladder back up after her and fastened the latch so it couldn’t be pulled back down, and so it wouldn’t fall down if Merrie stepped on it.

The little girl ran to the window and looked out.

“I see giraffes. An elephants and koala bears — red ones.”

“My, but we have an eclectic array of wildlife in our kingdom.”

“They’re not electric. Animals don’t have plugs. They have batteries.”

Merrie settled into her pretend role while Charlie considered how best to scoot what was already here around so she could bring up all things seamstress from downstairs to take its place. She had just about finished rearranging the attic contents when the box fell on her head.

It had been on the top of the chifforobe — which Charlie could only assume had been constructed in the attic because she could see no way that it could have been moved up the ladder from downstairs. It was next to the window that looked out over the backyard and the woods and mountain beyond. The dirt yard was getting green again, but Charlie didn’t look out the window. She still couldn’t look at the kiln without becoming almost physically sick, even after she’d gotten Lester Peetree from the hardware store to come over and remove the kiln door. It hadn’t been that hard to do working from the inside where you could get to the hinges. She would have hauled the whole thing off to the dump, but there was no way to pick it up and no dum

p in Nowhere County. She planned to take a sledgehammer to it and beat the whole thing into little pieces of rock … someday.

The big piece of furniture had double doors on the front and an interior that was reminiscent of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. It wasn’t too heavy now that it was empty. She set her back against the double doors and shoved with her legs. When she did, it tipped, and a box she didn’t know was up there slid off the top and crashed down onto her head.

It could have been a box full of bricks. Okay, realistically, it really could have been full of books or pottery. It was neither. It was a cardboard box full of papers and assorted junk and when it hit her head, the top flew open, and the box vomited its contents all over the floor. She rubbed the spot on her head where the box had clocked her, then got down on her hands and knees to pick up the spilled papers.

A picture drawn in crayon. Stick figures. “I love you Mommy” and a heart.

A penmanship paper. Did kids even use those anymore? “Mallory” was printed on the top and below it were sets of three lines, where you printed a letter in lowercase, so the top of the O fit beneath the middle dotted line, and the top and bottom of the O hit the top and bottom lines. School papers and things Mama had kept. Mallory’s third-grade report card. She opened it up. There was an S, which meant satisfactory, in every column. But an S- in the column “plays well with others.” Even as a kid, her older sister had had issues.

“Merrie, come help me put this stuff back in the box.”

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3)

Trapped (Nowhere, USA Book 3) Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2)

Mad Dog (Nowhere, USA Book 2) Black Water

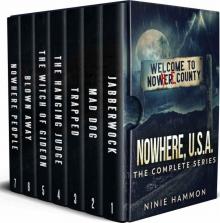

Black Water Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA)

Nowhere USA: The Complete Series: A Psychological Thriller series (Nowhere, USA) The Jabberwock

The Jabberwock Blue Tears

Blue Tears Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6)

Blown Away (Nowhere, USA Book 6) The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4)

The Hanging Judge (Nowhere, USA Book 4) Sudan: A Novel

Sudan: A Novel Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7)

Nowhere People (Nowhere, USA Book 7) The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5)

The Witch of Gideon (Nowhere, USA Book 5) Red Web

Red Web Gold Promise

Gold Promise All Their Yesterdays

All Their Yesterdays When Butterflies Cry: A Novel

When Butterflies Cry: A Novel Home Grown: A Novel

Home Grown: A Novel Five Days in May

Five Days in May The Memory Closet

The Memory Closet The Last Safe Place

The Last Safe Place The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material

The Knowing Box Set EXTENDED EDITION: Exclusive New Material